Hieroglyphics. Elemental Traits. Basic rules of calligraphy in Chinese

One of the main difficulties facing every Chinese language learner is mastering the Chinese characters, which have been the accepted writing system in China for at least three and a half millennia.

What are hieroglyphs? What is their specificity that distinguishes Chinese characters from other scripts of the world? To answer this question, you need to know that any writing system can be classified into one of two main types.

The first of them (phonetic) includes systems whose signs serve to record the sound of certain language units. These include alphabets, which include letters and record individual sounds (an example is the Chinese alphabet), and syllabaries, fixing whole syllables (this variety of phonetic scripts includes, in particular, Japanese katakana And hiragana).

The second type of writing (ideographic, or hieroglyphic) is characterized by the fact that signs serve to record the lexical meaning of speech units - syllables or words. The Chinese writing system is of this type.

Hieroglyphic writing differs from alphabetic or syllabic in that it includes significantly more signs. There can be two or three dozen letters in the alphabet, hundreds of characters in syllabic systems, and several thousand or even tens of thousands in hieroglyphic systems.

IN Chinese each significant syllable (morpheme) is conveyed by a separate hieroglyph; To write a word, you need as many characters as there are syllables in it. In total, the Chinese language has about 400 syllables that differ in sound composition; the presence of tones increases this number by three to four times. The number of different morphemes is many times greater, which is explained by the presence of homonyms. This is why there are so many characters in Chinese writing.

In the official list of only the most commonly used characters, there are 3000 of them. In order to read, for example, the People's Daily newspaper, you need to know at least 4 thousand characters, and in order to understand special or literary texts- and even more. In The Big Chinese-Russian Dictionary, ed. prof. Oshanin more than 40 thousand hieroglyphs; in Chinese explanatory dictionary"Kangxi zidian" - there are about 48 thousand of them.

The need to remember a large number of signs is one of the main difficulties associated with mastering the Chinese writing system.

At the same time, the majority Chinese characters are complex in structure, which makes them difficult to memorize.

If you don’t remember something from this lesson, it’s okay, just move on to the next one (you don’t need to do this with the next ones!)

Elementary Traits

Main features

For all their apparent diversity, modern Chinese characters are combinations of a certain number of strictly defined elementary characters. crap. There are only eight main features:

| horizontal | 二五百 | |

| vertical | 千士巾 | |

| tilting to the right | 欠又文 | |

| tilting to the left | 成石九 | |

| oblique intersecting | 戈戰戒 | |

| ascending | 冰決波 | |

| dot right | 六玉交 | |

| dot left | 心小亦 |

In the first column - the trait, in the second - its name, in the third - examples.

Traits with a hook

Some traits have spelling variations. So, horizontal, vertical and folding to the right can end with a slight bend - "hook". There are a total of five such traits with a hook:

broken lines

In addition to the main features and their variants with a hook, in hieroglyphs there are continuous spellings of several features, which we will call broken lines. There are six such traits:

The name of a broken line (horizontal, vertical, folding) is given by its initial part.

Broken lines with a hook

Broken features can also be combined with a grappling hook. There are only five such traits:

These 24 features make up all Chinese characters in their modern spelling.

The number of strokes that form modern Chinese characters can vary greatly. If in the most simple hieroglyphs in their structure there are one or two lines, then in the most complex there can be two or three dozen or even more. For example, the sign "bright" consists of 28 lines, and "stuffy nose" of 36! However, such examples are by no means isolated.

It is very important to learn how to quickly and accurately identify the constituent features of the hieroglyph and correctly count them. total number, because in many dictionaries, library catalogs, etc., hieroglyphs are arranged in ascending order of the number of strokes.

In addition, when prescribing hieroglyphs, it is necessary to strictly observe the sequence of strokes.

Basic rules of calligraphy

The sequence of writing strokes as part of a hieroglyph is subject to strict rules:

It should be borne in mind that a hieroglyph of any complexity, regardless of the number of its constituent features, must fit into a square of a given size. It is recommended to write hieroglyphs on squared paper, allocating four cells for each hieroglyph and making a gap between the hieroglyphs. Graphic elements in signs with a small number of strokes should be written enlarged, and in complex signs - compacted.

For example:

口 器 讓 聲 敬 句

Tasks and exercises

The art of calligraphy

When we talked about calligraphy above in connection with the analysis of Chinese characters, we had in mind, first of all, the observance correct sequence their constituent elementary features. But the term "calligraphy", as you know, has another meaning - the ability to write not only correctly, but also beautifully. In China, calligraphy has long been one of the traditional species high professional art, along with painting.

It is impossible to imagine the traditional Chinese painting without virtuoso hieroglyphs written on it; and inscriptions in a variety of handwritings still adorn the study of a scientist in China or are hung on the doors of houses on major holidays.

And this is no coincidence. Hieroglyphs provide abundant food for the perception of them not just as signs of writing, but as certain artistic images containing no less diverse information than the text itself, and capable of delivering aesthetic pleasure.

The high standards that were traditionally set for everyone who sat down at the desk required the obligatory mastery of special skills, and they were given by years of hard training.

It is not surprising that in China the ability to write hieroglyphs correctly and beautifully has always been considered and is still considered an essential sign of intelligence. It is known that many famous European writers and statesmen there was a disgusting handwriting, which, apart from themselves, few could make out. In China, where the cult of learning was associated with the art of calligraphy, this was simply not possible.

Anyone who has taken up the study of the Chinese language should pay close attention to hieroglyphics - the most valuable cultural heritage China, its invaluable contribution to the treasury of world civilization.

Since Chinese is a language that does not have a strict phonetic alphabet, it frightens many learners because of its particular complex system letters. Chinese characters (汉字 Hanzi or "Han characters"), better known as logograms, where each character represents one morpheme (i.e., a meaningful unit of language), are mainly used in Chinese and partly Japanese writing. It is one of the most multi-character known writing systems. The number of Chinese characters in the famous Kangxi Dictionary (康熙字典 Zìdiǎn Kangxi, commissioned by Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty) is about 47,035. So what makes Chinese characters so difficult? First, we need to understand what the Chinese character means: 1) determine its value from the form In the case of the character 爱, for example, you need to determine the meaning, i.e. "love", to know that it is pronounced as ài with a fourth tone (falling), and finally, also to know that this character consists of 9 strokes, which must be written from top to bottom and from left to right. He won't be able to pronounce it unless he has its numeric form, or he doesn't use software to determine how each character is pronounced, or he doesn't have pinyin text (a system for phonetic transcription and transliteration of Chinese characters into Latin) (see also here to hear the sounds). The traditional way to start learning Chinese characters is that each character is an independent character: some learn and memorize them by repeatedly writing one after the other. This rote memorization is based on lists in which they come in order of difficulty and frequency. This is the path of various language courses and universities. They are often considered separately from each other and out of context. This approach does not achieve main goal learning - to use this language as a means of communication. Thus, learning in the above way is not only of little use, but it also slows down the acquisition of the language itself. New offer Stage 1 - Text analysis I will try to show you part of this resource. If you find text in Chinese characters online, the resource will provide very useful and effective tools to not only translate the entire text into Latin letters, but also show the meaning of each letter or two or three letters (if the word consists of 2 or even 3 syllables) through pop-up windows. The entire text can be printed out and accompanied by a dictionary underneath! (Mandarinspot). And that is not all! If there is no audio, you can also copy the text into a suitable voice synthesizer window for reading. You will find an example. And last but not least, Google Translate provides a draft translation of the text. Computer programs work especially well with languages that have a relatively simple syntactic structure, such as Chinese. If your text is not in digital format and you are working with a simple textbook that provides you with a translation into your native language, the algorithm is largely the same: you need to read the Chinese (L2) text to understand and analyze general meaning and the meaning of the individual parts by comparing the two languages. It is very important to point out that the ability to translate text, accompanied by an explanation of words and grammar rules, is drastic change, in that it allows the student not to use dictionaries. Looking up a word in a Chinese dictionary can be quite a long and tedious task. The student should be able to extract the so-called "root" from a character and then search for it based on the number of strokes. Phase 2 - Synthesis Once you've got hold of these tools, you only need to create the usual, cyclical and dynamic way that allows you to refer, session after session, text in many ways. Steps (steps) on how to deal with this text can be done as follows: On a final note, if you need to improve your Chinese handwriting (for university exams or other reasons), you can add two more steps to the above chart: Finally, if you need to know the move in order to certain nature, you can use Arch alone, which provides amazing animations on how to write it, as well as informing you about various information about it (difficult words, phrases containing it, etc.).. The number of characters to remember remains high, however Chinese writing is quite rational, and once you've figured out the way the individual components are put together, acquiring the characters becomes easier and faster. It's just a matter of practice, having the right tools and motivation.. and the rest will come. Stay tuned for the next post: tips on how to learn tones the right way from the start Conceived and written by Luca Lampariello e Luca Toma

Automatic translation from Googleoogle

2) understand intonation and pronunciation based on the context (the same character can have different pronunciations)

3) understand how to write it (sequence of strokes)

The first hurdle in learning Chinese is the complete absence of any kind of guidance. A beginner may encounter the following sentence:

我是意大利人 (I am Italian)

A classic question for Chinese speakers or learners: "How many characters do you know?"

This is a question that reflects general idea- most often misunderstood - about Chinese learning, namely that the number of characters you know is an indication of your actual knowledge of the language. Well, this is a false myth that needs to be dispelled.

In any case, before talking about the writing system and analyzing its difficulties, we must first talk about the nature of the Chinese language. Chinese is considered an isolating language, that is, a language that has neither inflections nor declensions, in which there is practically no morphology. If we think of the morpheme as the smallest unit that defines meaning, then in isolating languages words cannot be broken down into smaller morphological units. Most often, in such languages, the word is expressed not through modifications (suffixes, endings, etc.), but in accordance with the position it occupies in the sentence. Obviously, the fundamental building block in languages like Chinese is the individual character. This aspect becomes even more evident in Classical Chinese, where each idea corresponds to one syllable and thus one character, while Modern Chinese tends to form compound words of two or three syllables.

I should also note that this way of learning how to write Chinese characters by hand is quite demanding and tedious, especially in the early stages of learning. In fact, this type of "kinesthetic" activity can be useful for storing characters in memory (the brain connects the movements of the hand to write all the elements in order, line by line, which at the end gives the character itself), but this entails a systematic effort. and a huge load on our memory. It should, in fact, not only remember how to write each character (number of elements, their order, etc..), but also its meaning, pronunciation, and tone.

What I am suggesting here is the dynamic learning of Chinese characters, which is much more efficient and much less pedantic than the academic approach. The training is divided into the corresponding stages:

In the so-called analytical phase, you read the text in the original language (L2), analyze each part in detail (words, structures, etc.), and then translate it into your own language. native language(L1). The key, especially in the case of Chinese, is finding text with characters, pinyin, and audio. So you will be in best conditions to understand what you are learning. Thus, the Internet has revolutionized the study of languages. And there is still a "quiet" revolution due to the fact that people have not figured out how to benefit (properly use) such a huge source.

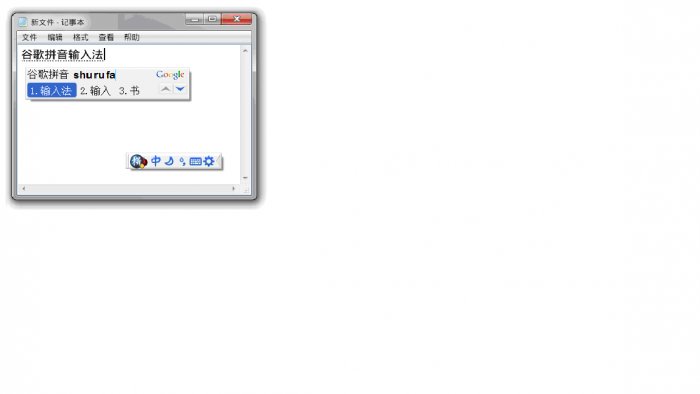

In synthesis, you read text into your native L1 language and translate it back into target language(L2). In the case of Chinese, it is recommended to work on the computer using software input. For Chinese, the easiest and most intuitive tool is undoubtedly Google Google Pinyin Pinyin ( http://www.google.com/intl/zh-CN/ime/pinyin/). You can add an alternative Chinese language bar to Windows (Control Panel > Regional Language Options > Languages tab > Details > "Add").

This technology allows you to write directly in Chinese on a word file by typing with Latin letters, that is, in pinyin. If you know how to pronounce the characters, you can easily write Chinese text in a word processor. Carrying out this operation is very useful. By doing so you not only continue to internalize the pronunciation of the characters (through numerous reading and listening sessions), but it will also help you to recognize and recognize the right characters among the many that correspond to homonyms. Saturation of this effort allows the brain to form a connection between the sounds (pinyin) and the shapes associated with it (hanzi) in a less stressful and much more efficient and natural way than out of context rote memorization is done by more) traditional studies.

Session 1 - listening and reading (versus translation, sentence by sentence in L1)

Session 2 - analysis (phrase by phrase, revealing unknown structures and terms)

Session 3 - review (listening and reading, pinyin only)

Session 4 - translation L1 (sentence by sentence regardless of existing translation)

Session 5 - review (listening and reading)

Session 6 - L2 synthesis (translation, pinyin sentence by sentence and final error checking)

I strongly advise you to ignore Chinese characters for the first 3-4 months of learning, focusing solely on phonetic writing (pinyin). The main goal at the very beginning is to first learn the sound of the word (as well as its meaning), and only then the character, or symbols associated with it.

Thus, in the first months, you will only write the pinyin translation, without using Google pinyin. You can just type the tones in a row (example: 我是意大利人: WO3 shi4 yi4da4li4 ren2) .. After you get familiar with pinyin, you can take the next step, use Google pinyin and write real characters. At this point, you can look back and check old texts by looking at the characters and their Google pinyin translation.

Session 1 - listening and reading (versus sentence-by-sentence translation in L1)

Session 2 - Analysis (phrase by phrase showing unknown structures and conditions)

Session 3 - review (listening and reading, pinyin only)

Session 4 - L1 translation (sentence by sentence without looking at the translation)

Session 5 - review (listening and reading)

Session 6 - Synthesis L2 (translation, pinyin sentence by sentence and final error checking)

Session 7 - copy text to symbols

Session 8 - write the text of the characters from the version in pinyin

I decided to write a trial lesson for those who are going to or just starting to learn Chinese. It won't be educational materials classic style with detailed description completely unnecessary information. Only information of practical interest will be presented. Some points of Chinese grammar, vocabulary and other disciplines can be deliberately simplified or presented subjectively.

Before you start learning Chinese, I strongly recommend that you read the following articles:

Chinese. Introduction ()

Learning Chinese Visually ()

In my opinion, existing textbooks immensely complicate the process of learning Chinese by trying to simultaneously give a lot of knowledge that is better spread in space and time. That is why in the first lessons nothing will be said about pronunciation. The goal of the first stage is to gain a hieroglyphic base. The pronunciation information will be given very conditionally, it will be based on the Chinese transcription of pinyin and the Russian transcription developed by Palladius, and will completely ignore tones.

Reference Information:

Pinyin- the Chinese system for recording the pronunciation of hieroglyphs based on letters Latin alphabet(an exception is the letter ü “u-smart”). Note: Don't try to read pinyin in English.

Transcription of Palladium- Russian system for recording the pronunciation of Chinese characters, adopted in Russia. It was first used in the Chinese-Russian dictionary of 1888 compiled by Archimandrite Pallady. Very conventionally conveys the Chinese pronunciation.

Tones in Chinese- a system of pronunciation of a Chinese syllable, in which the same syllable can have up to four different intonational sounds, which allows you to put different informational meanings into the same syllable. For the Chinese language, this is very important, since the number of syllables in it is limited and is about 400.

So, you need to memorize the reading of pinyin according to Palladium. To do this, I will give a reading of the hieroglyph in the form Hieroglyph - Pinyin - (Palladium), for example: 道 dao (tao). That is, you need to remember that dao is read as dao. Palladium is given for guidance only. Remember pinyin, because it is extremely important in the future practical study of the Chinese language, and you will rarely see Palladium in the future.

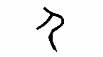

Each new character will be accompanied by a picture with its correct spelling. It is also desirable to memorize the inscription sequence, since there are two main ways of computer typing of hieroglyphs - by pinyin and using the system handwriting. If you do not remember the pronunciation, you can type a character by drawing it, and for this it is highly desirable to know the sequence of its writing, because it is taken into account by the computer during recognition. Do not pay attention to thickenings in the lines, these prettinesses imitate the writing of a hieroglyph with a brush, ordinary lines are written with a pen.

Let's start with the character 人 - a person that reads like ren (ren).

All hieroglyphs originated from images. In ancient written monuments a person was portrayed as a person:

As we can see, the modern hieroglyph "man" has not changed much over the past millennia.

Next hieroglyph:

口 kou (kou) mouth

Please note that it consists of three traits, and not four, as one would expect.

Compared to ancient times, the hieroglyph has also changed little.

Knowing two characters, we can already compose a Chinese word. In modern Chinese, most words consist of two characters. This is dictated by the fact that the number of syllables in Chinese is limited, and many hieroglyphs have the same reading. Therefore, it is not necessary to translate the hieroglyphs separately. They are usually included in words.

So the first Chinese word is:

人口

A hieroglyph, unlike a letter, is a symbol. And therefore, it carries the ambiguity of meanings, which must always be taken into account when memorizing and translating new words. This word has three main meanings:

Literal, "human mouth" or simply "mouth, mouth".

figurative, a certain human unit that consumes food. Fits perfectly Russian word"eater".

Contemporary, "population". Under modern meaning I understand the most common in modern Chinese.

Oshanin's largest Chinese-Russian dictionary gives one more meaning, exotic, "voice of the people". But, I think that such a meaning can only come across to you when reading ancient Chinese texts.

So, let's focus on the most common sense 人口 ren-kou population. I gave the rest of the examples only so that you have an idea of the ambiguity of not only hieroglyphs, but also Chinese words. Therefore, if the meaning of the text, which seems to consist of words familiar to you, remains unclear, the most correct thing is to check their meanings in a dictionary. In the future, I will give only the most common translations of words and hieroglyphs.

Next hieroglyph:

心 xin (blue) heart

Isn't it true that its ancient spelling

looks like a real heart)) And there is a certain connection with modern writing?

Now let's see what new words we can make from the studied hieroglyphs:

心口 In this example, you will have to turn on the creative thinking. The heart is the soul, the mouth is speech. The soul, as a silent entity, cannot prevaricate. But the mouth very often does not say what the person thinks. Therefore, the correct translation would be "thoughts and words."

人心 human heart are “feelings, thoughts, desires”. This is the correct translation.

It must be borne in mind that the grammatically Chinese language is very primitive. It has practically no means for expressing the plural. So don't be afraid to use plural when translating words where it is appropriate and dictated by the meaning.

Next hieroglyph:

中 zhong (zhong) middle, center. I think the meaning of the image is clear without additional comments.

This hieroglyph also has not undergone significant changes over the centuries.

![]()

The following combinations are possible with this hieroglyph:

人中 among people

中人 person of average ability

心中 in the heart, in the soul; inside

中心 middle, center

Do not think that any hieroglyph forms a pair with any other hieroglyph.

Please note that the location of the hieroglyph in the word gives completely different meanings. Speaking specifically about 中, then located in the first place, it carries more of a connotation of the adjective, and in the second place - an indicator of place.

Next hieroglyph:

文 wen (wen) writing.

The hieroglyph originally depicted a tattoo on the body, as you can see from the picture. So we can say that the Chinese script originated from the tattoo on the body of the Chinese leader))

With this hieroglyph, we can get the following pairs:

人文 human culture, civilization.

文人 educated, man of culture. In these two words, 文 appears in a very broad sense: literacy as necessary condition for the emergence of culture.

中文 Chinese. Here 中 acts as a synonym for China, because the Chinese call their state the middle one, located in the center of the world.

Well, now the simplest Chinese character:

一 yi (and) one.

It has remained unchanged since antiquity.

![]()

Let's see what pairs there are with this hieroglyph:

一人 one person, someone. The hieroglyph “one” can also act as an indicator of the uncertainty “someone, some”, like the Russian “one - once”.

一口 unanimously.

一心 with all my heart, unanimously.

Next hieroglyph:

大 da (yes) big

The meaning of the hieroglyph is also transparent, depicting a man with arms wide apart.

大人 adult, adult.

一大 sky. This example is very interesting. To understand why the combination "one - big" means "sky", let's move on to studying the next hieroglyph.

Next hieroglyph:

天 tian (tian) sky

Depicts something that is above the crown of a person. That is the sky.

All Chinese characters can be divided into two parts - indivisible and composite. Indivisibles are those that cannot be broken down into simpler constituent parts. All the hieroglyphs that we have studied so far were indivisible. Although it would seem that 大 can be divided into 一 and 人, the Chinese consider it indivisible. But the character 天 is already a composite character, it consists of 一 and 大. One of the elements that make up composite hieroglyphs is considered by the Chinese to be the key. Knowing the key in the hieroglyph is absolutely necessary if you use Chinese paper dictionaries, where the hieroglyphs are located exactly by the keys. In the character 天, the element 大 is such a key. Therefore, in the future, I will place the key of the hieroglyph in brackets after the translation in the form:

天 tian (tian) sky (大)

And if there is no such clarification, then the hieroglyph is indivisible.

I hope now it is clear why 一大 means "sky", it's just the character 天 decomposed into its component parts.

天人 an outstanding person; celestial

天口 skillful orator, Chrysostom

天心 center of the sky, zenith

天中 center of the sky, zenith

astronomy

Next hieroglyph:

日 ri (zhi) the sun. “Day” also matters, since the rotation of the Earth around its axis is associated with the movement of the sun across the sky and the calculation of days.

The sun is the sun

日人 Japanese. Japan is also associated in China with the sun, just as China is with the center of the world, so 日人 will not be a sunny person, but a Japanese.

日心 heliocentric

noon

中日 Sino-Japanese

日文 Japanese

Next hieroglyph:

女 nü (nu) woman.

In ancient times, it was depicted as a submissive figure, squatting.

女人 woman; wife

女口 female chatter

天女 goddess, fairy

Next hieroglyph:

如 ru (zhu) to resemble, to be like, to match (女)

Please note that these are not two characters 女口, but one compound.

IN ancient China a daughter was to obey her father, a wife to her husband, and a widow to her son. Therefore, the joint image of a woman and a mouth (father, husband, son) carried a meaning - to follow in accordance with the instructions, to correspond to one's status of implicitity.

如心 correspond to desire.

如一 the same, no change

The studied hieroglyphs are already enough for us to read the phrase more complicated than simple words. Here she is:

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

After the native and flexible Russian language, the first phrases in Chinese are more like Russian Chukchi. In fact, well, what is it: To be like - the sun - the middle - the sky. There are not enough endings, declensions, conjugations and other means that make the phrase understandable and rounded. And here chopped style without any hint of beauty. So, correct translation the phrase "Like the sun at its zenith." That is, to be in full bloom of something. Looking ahead, I want to reassure you that in its expressiveness, elegance and beauty, the Chinese language is in no way inferior to Russian, but it achieves this by other means.

Four-character phrases like the one we have translated are very common in Chinese and are called chengyu. Most of them are quotations from Chinese classics, and favorite hobby Chinese lexicographers - to compile monstrous thickness dictionaries in which pedantically describe the origin of chengyu.

So, today we learned 12 hieroglyphs:

人口心中文一大天日女如

Afterword on Silence

A few words to justify the fact that oral Chinese is not required to be studied at the first stage.

As you already understood, I propose now to limit ourselves to the hieroglyphic base, without studying pronunciation. Anticipating criticism of this provision, I would like to state my arguments in some detail.

In my opinion, it is completely irrational to study Chinese in its entirety from the first steps. In order to learn how to say a few banal phrases in Chinese, you must first understand the system of tones, the rhythm of the sentence, learn to associate hieroglyphs with their sound. At the first stage, this is completely unnecessary attempts.

The study of Chinese oral speech, I would decompose into two stages.

First. passive perception. When your character base is so good that you can understand the main content with fluent reading, it's time to start listening to Chinese speech. In this case, for example, when watching programs with subtitles, your perception no longer needs to be torn between the translation of the text and its comparison with the sound. It can fully concentrate on the intricacies of spoken Chinese.

When you can already understand at least 50 percent of the conversation, you can move on to trying to squeak something in Chinese yourself. Here, again, perception is focused on only one task, which makes the learning process easier and more efficient.

If you think that palladium transcription will in the future be a force majeure obstacle to the correct learning of spoken Chinese, then this does not seem to be a serious problem. In the early stages, we all speak with a monstrous Russian accent, no matter what language we study. Therefore, the transcription of Palladium can only be considered as a Chinese text with a Russian accent, from which it will not be more difficult to switch to pure Chinese speech than in the classical study of the language.

Good luck in the difficult and meaningless work of learning Chinese))

Criticism, enthusiastic screams and spitting will be received with gratitude, as well as links to this article posted on the Internet.