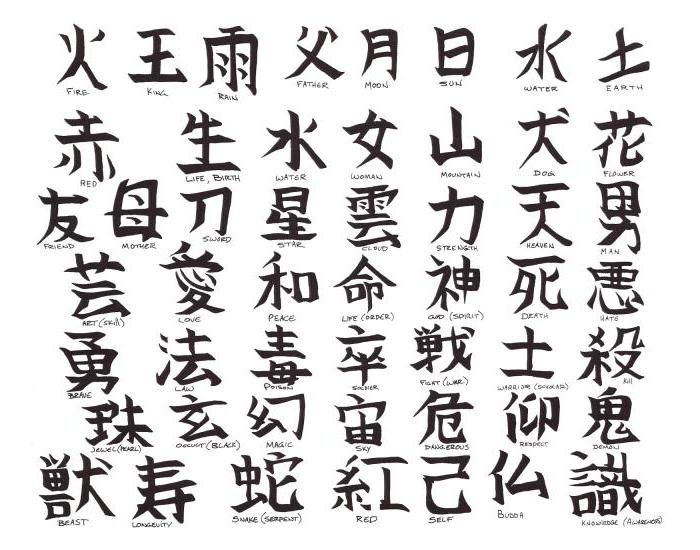

What do japanese characters mean. Japanese characters

Kanji(jap. 汉字 - kanji, "Chinese characters") - hieroglyphic writing, component Japanese writing.

Japanese characters were borrowed by the Japanese in China in the 5th and 6th centuries. Hieroglyphs developed by the Japanese themselves (国字 - kokuji) were added to the borrowed signs. In addition to hieroglyphs, two components of the alphabet are also used for writing in Japan: hiragana and katakana, Arabic numerals and Latin alphabet romaji.

Story

The Japanese term kanji (汉字) translates as "Signs (of the dynasty) of Han". It is not known exactly which way Chinese characters came to Japan, but today the generally accepted version is that the first Chinese texts were brought at the beginning of the 5th century. These texts were written in Chinese, and in order to be able to read them using diacritics while respecting the rules of Japanese grammar, the kanbun system was developed - kanbun or kambun (汉文) - originally meant "Classical Chinese composition".

The Japanese language at that time did not have a written form. To record the original Japanese words, the Man "yōshū (万叶集) writing system was created, the first literary monument of which was the ancient poetic anthology Manyoshu. The words in it were written in Chinese characters in sound, and not in content.

Man "yōshū (万叶集) Russian Manyoshu, written in hieroglyphic cursive, turned into hiragana, a writing system for women who had almost no higher education. Most literary monuments Heian eras with female authorship were written in hiragana. At the same time, Katakana arose: students from monasteries simplified Manyoshu to a single significant element. These writing systems, katakana and hiragana, evolved from Chinese characters and subsequently evolved into syllabic alphabets, which together are called Kana (仮名), or Japanese syllabary.

Hieroglyphs in modern Japanese are used for the most part to write the stems of words in nouns, adjectives and verbs, on the other hand, hiragana is used to write inflections and endings of verbs and adjectives (see okurigana), particles and words in which it is difficult to remember hieroglyphs. Katakana is used to write onomatopias and gairago (loanwords).

The use of katakana for writing borrowed words is relatively recent. By the end of World War II, such words were written in hieroglyphs by meaning (烟草 or 莨 tabaco - "tobacco", literally "grass, smokes") or by phonetic sound (天妇罗 or 天麸罗 tempura - fried food of Portuguese origin). The last way to write hieroglyphs is called ateji.

Japanese innovation

At first, Chinese and Japanese characters were practically no different from each other: the latter were traditionally used to write Japanese text. However, there is currently a difference between Chinese Hanzi and Japanese Kanji. a big difference: Some characters were created by the Japanese themselves, and some have received a different meaning. In addition, after the Second World War, many Japanese characters in writing were simplified.

Kokuji (国字)

Kokuji (国字 - "national hieroglyphs") are hieroglyphs of Japanese origin. Kokuji is sometimes referred to as Washa kanji (和制汉字 - "Chinese characters created in Japan"). Altogether there are several hundred kokuji. Most of them are rarely used, but some have become important additions to written Japanese. Among them:

峠 (とうげ) toge (mountain pass)

榊 (さかき) sakaki (sakaki tree from the Camellia family)

畑 (はたけ) hatake (dry field)

辻 (つじ) Tsuji (crossroads)

働 (どう/はたらく) do, Hatar(ku) (physical work)

Most of these "national characters" have only Japanese readings, but some were borrowed by the Chinese themselves and acquired onne (Chinese) readings as well.

Kokkun (国训)

In addition to kokuji, there are characters that have a different meaning in Japanese than in Chinese. Such hieroglyphs are called kokkun (国训 - "[signs] of national reading"). Among them:

冲 (おき) OKI (open sea; Chinese rinse)

森 (もり) Sea (forest; Chinese majestic, lush)

椿(つばき) Tsubaki

Old and new characters (旧字体, 新字体)

The same character can sometimes be written different styles: old (旧字体, kyujitai - "old characters"; in the old style 旧字体) and new (新字体, shinjitai - "new characters"). Below are several examples of writing the same character in two styles:

国 (old) 国 (new) kuni, koku (country, region)

号 (old) 号 (new) go (number, name, name)

变 (old) 変 (new) hen, ka (wara) (change, vary)

Old-style Japanese characters were used until the end of World War II and, for the most part, are the same as traditional Chinese characters. In 1946, the Japanese government legislated the simplified new style characters in the "Toyo Kanji Jitai Hyo" (当用汉字字体表) list.

Some of the new signs matched the simplified Chinese characters used today in the PRC. As a result of the PRC's writing reform, a number of new characters were borrowed from cursive forms (略字, ryakuji) that were used in handwritten texts. However, in a certain context, the use of the old (correct) forms of some hieroglyphs (正字, Seiji) was also allowed. There are also even more simplified versions of writing hieroglyphs, however, the scope of their use is limited to private correspondence.

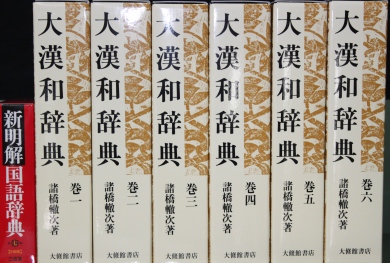

Theoretically, any Chinese character can be used in Japanese text, but in practice, a lot of Chinese characters are not used in Japanese. Daikanwa jiten (大汉和辞典) - one of the largest dictionaries of hieroglyphs - contains about 50 thousand characters, but most of them are rarely found in Japanese texts.

Reading hieroglyphs

Depending on how the character got into Japanese, it can be used to write one or different words, and even more often morphemes. From the reader's point of view, this means that the hieroglyphs have one or more readings. The choice of reading a hieroglyph depends on the context, content and communication with other characters, and sometimes on the position in the sentence. The reading is divided into two: "Chinese-Japanese" (音読み) and "Japanese" (訓読み).

Onyomi

Onyomi (音読み - phonetic reading) is a Sino-Japanese reading or Japanese interpretation of the Chinese pronunciation of a character. Some characters have multiple onyomi because they were borrowed from China several times, in different time and from different areas. Kokuji, or characters that the Japanese themselves invented, usually do not have onyomi, although there are exceptions. For example, in the character 働 "work" is kunyomi (hataraku), but there is also onyomi, but in the character 腺 "gland" (mammary, thyroid, etc.) is only onyomi.

Kunyomi

Kunyomi (訓読み) is a Japanese reading, which is based on the pronunciation of native Japanese words (大和言葉, yamato kotoba - "Yamato words"), to which Chinese characters were chosen for meaning. In other words, kunyomi is the translation of the Chinese character in Japanese. In several hieroglyphs, there may be several kunyomi at once, or there may not be at all.

Other readings

There are a lot of combinations of hieroglyphs, for the pronunciation of the components of which both onyomi and kunyomi are used. Such words are called "zubako" (重箱 - "loaded chest") or "yuto" (汤桶 - "boiling water barrel"). These two terms themselves are autological: the first sign in the word "zubako" is read in onyomi, and the second - in kunyomi. In the word "yuto" - on the contrary. Other examples of such mixed readings: 金色 kinyiro - "golden", 空手道 karatedo - "".

Some kanji have a little-known reading - nanori (名乗り - "name name"), which is usually used when voicing personal names. As a rule, they are close in sound to kunyomi. Toponyms also sometimes use nanori, or even such readings that are not found anywhere else.

Gikun (义训) - reading the messages of hieroglyphs that are not directly related to the kunyomi or onyomi of individual characters, but related to the content of the entire hieroglyphic combination. For example, the combination 一 寸 can be read as "issun" (that is, "one sun"), but in reality this indivisible combination is read as "tyotto" ("a little"). Gikun is often found in Japanese surnames.

The use of ateji to write borrowed words resulted in new meanings in characters, as well as messages that were unusual to read. For example, the obsolete message 亜细亜 aji was previously used for hieroglyphic writing of the part of the world - Asia. Today, katakana is used to write this word, but the sign 亜 has taken on a different meaning - "Asia", in combinations such as "TOA" 东亜 ("East Asia").

From the obsolete hieroglyphic combination 亜米利加 (America - "America"), a second sign was taken, from which the neologism 米国 (beikoku) arose, which can literally be translated as "rice country", although in reality this combination means the United States.

Choice of options

Words for similar concepts such as "east" (东), "north" (北), and "northeast" (东北) can have completely different pronunciations: Higashi and kita are kunyomi readings and are used for the first two characters, while while "northeast" would be read in onyomi - Tohoku. Choosing the correct reading for a character is one of the most difficult aspects of learning Japanese.

As a rule, when reading combinations of hieroglyphs, onyomi are selected. Such messages are called Japanese jukugo 熟语. For example, 学校 (Gakkō, "school"), 情报 (Joho, "information"), and 新干线 (Shinkansen) are read in this pattern.

The hieroglyph, which is located separately from other hieroglyphic signs and surrounded by Kana, is usually read in kunyomi. This applies to nouns as well as conjugated verbs and adjectives. For example, 月 (tsuki, month), 新しい (atarasii, "new"), 情け (nasak, "pity"), 赤い (akai, red), 見る (measure, "look") - in all these cases, kunyomi is used.

These two basic pattern rules have many exceptions, and kunyomi can also form compound words, although they are less common than the onyomi message. Examples include 手纸 (tagami, "letter"), 日伞 (Higashi, "solar umbrella"), or the famous phrase 神风 (kamikaze, "divine wind"). Such messages may also be accompanied by okurigana. For example, 歌い手 (hidden, "singer") or 折り紙 (origami). However, some of these combinations can be written without it - for example, 折纸 (origami).

In addition, some hieroglyphs that stand separately in the text can also be read for onyomi: 爱 (ai "love"), 禅 (zen), 点 (ten "mark"). Most of these hieroglyphs simply do not have kunyomi, which eliminates the possibility of error.

In general, the situation with the reading of onyomi is quite complicated, since many signs have several such readings. For comparison - 先生 (sensei, "teacher") and 一生 (issho, "all life").

In Japanese, there are homographs that can be read differently depending on the meaning, as in Russian "castle" and "castle". For example, the combination 上手 can be read in three ways: Uwat ("upper part, superiority") or kami ("upper part, upper course"), jozu ("skillful"). Additionally, the combination 上手い can be read as Umai ("skillful").

Some well-known place names, including (东京) and (日本, nihon or sometimes nippon) are read in onyomi, although most Japanese place names are read in kunyomi (for example, 大阪 Osaka, 青森 Aomori, 広島 ). Surnames and given names are also usually read in kunyomi. For example, 山田 is Yamada, 田中 is Tanaka, 铃木 is Suzuki. However, sometimes there are names that mix kunyomi, onyomi and nanori. You can read them only with a certain experience (for example, 大海 - Daikai (on-kun), 夏美 - Natsumi (kun-on)).

Phonetic cues

To avoid inaccuracies, along with hieroglyphs in the texts, there are sometimes phonetic clues in the form of hiragana, which are typed in a small “agate” size above the hieroglyphs (the so-called furigana) or in one line with them (the so-called kumimoji). This is often done in texts for children learning Japanese and in manga. furigana is sometimes used in newspapers for rare or unusual readings, as well as for hieroglyphs not included in the list of basic hieroglyphs.

Number of characters

The total number of existing hieroglyphs is difficult to determine. The Daikanwa jiten Japanese dictionary contains about 50,000 characters, while more complete modern Chinese dictionaries contain more than 80,000 characters. Most of these characters are not used in modern Japan, nor in modern China. In order to understand most Japanese texts, it is enough to know about 3 thousand hieroglyphs.

Spelling reforms

After World War II, starting in early 1946, the Japanese government began to develop spelling reforms. Some characters received simplified spellings called "shinjitai" (新字体). The number of characters used was reduced, and the lists of hieroglyphs required for study at school were approved. Shape variations and rare marks have been officially declared undesirable for use. main goal reforms was unification school curriculum studying hieroglyphs and reducing the number of hieroglyphic signs that were used in literature and the media. These reforms were advisory in nature. Many hieroglyphs not included in the lists are still known and often used.

Kyoku Kanji (教育汉字)

Kyoku kanji (教育汉字, "educational characters") - the list consists of 1006 characters that Japanese children learn in elementary school (6 years of study). This list was first established in early 1946 and contained a total of 881 characters. In 1981, it was increased to the current number. This list is divided by year of study. His full name is "Gakunenbetsu kanji" (学年别汉字配当表, "Table of characters by year of study")

Joyo kanji

Jyoyo kanji (常用汉字, "constant use characters") - the list consists of 1945 characters, which includes "Kyok kanji" for elementary school and 939 signs for high school (3 years of study). Characters that are not included in this list are usually accompanied by a furigana. The list was updated in early 1981, thus replacing the old 1850 character "Toyo kanji" (当用汉字), which was introduced in early 1946.

Jimmyo kanji (人名用汉字)

Jimmeyo kanji (人名用汉字, "characters for human names") - the list consists of 2928 characters, 1945 characters that completely copy the list of "jioyo kanji", and 983 characters are used to write names and toponyms. In Japan, most parents try to give their children rare names, which includes very rare hieroglyphs. To facilitate the work of registration and other services that do not have the necessary technical means for typing rare characters, in 1981 a list of "jimmeyo kanji" was approved, according to which newborns could only be given names with characters from the list, or hirigana or katakana characters. This list is regularly updated with new characters, and the widespread introduction of computers with Unicode support has led the Japanese government to prepare to add 500 to 1000 new characters to this list in the near future.

Gaiji (外字)

Gaiji (外字, "external characters") are characters that are not represented in existing Japanese encodings. These include variant or obsolete forms of hieroglyphs that are needed for reference books and references, as well as non-hieroglyphic characters.

Gaiji can be either user or system based. In both cases, there are problems with data exchange, this is because the code tables used for gaiji are computer and operating system dependent.

Nominally, the use of gaiji is prohibited by JIS X 0208-1997 and JIS X 0213-2000, as they occupy code slots reserved for gaiji. However, gaiji continue to be used, for example in the "i-mode" system, where they are used for pictorial signs. Unicode allows gaiji to be encoded in a private area.

Character classification

The Buddhist thinker Xu Shen (许慎) in his work Interpretation of Texts and Parsing of Signs (说文解字), divided Chinese characters into "six spellings" (六书, Japanese Rikusho), that is, six categories. This traditional classification is still used, but it hardly correlates with modern lexicography - the boundaries of the categories are quite blurred and one hieroglyph can belong to several of them at once. The first four categories relate to the structural structure of the character, and the remaining two categories to its use.

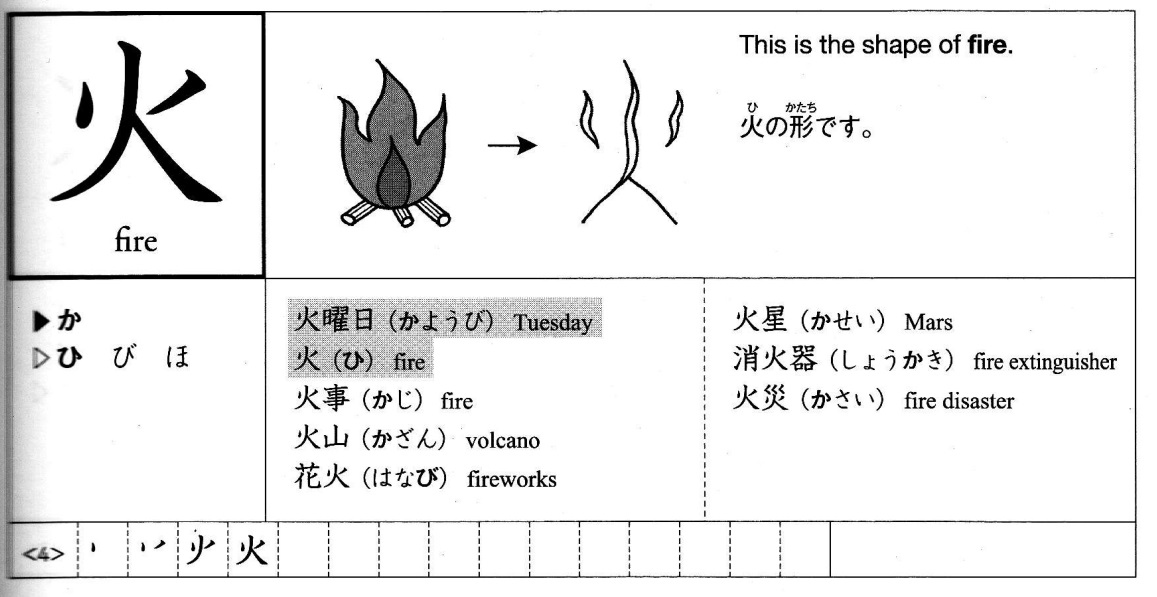

Pictogram script "seki moji" (象形文字)

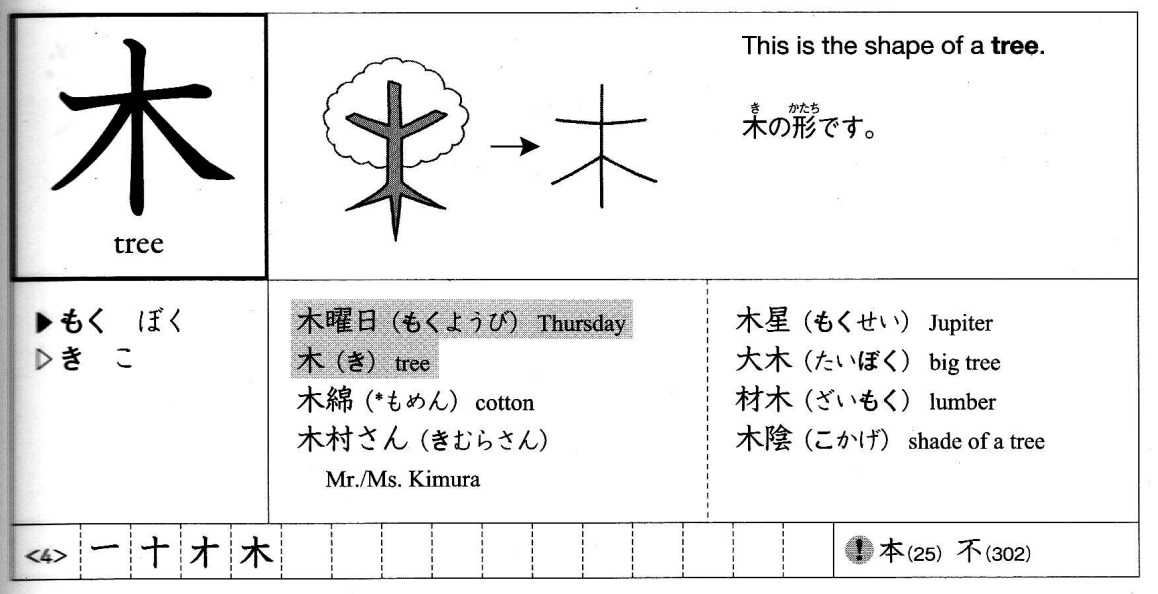

The hieroglyphs "seki moji" (象形文字) are a schematic representation of the depicted object. For example, 木 - tree or 日 - sun, etc. The original drawings differ significantly from modern forms, so unravel these hieroglyphs and their meaning by appearance hard enough. With signs in print, the situation is much simpler, they sometimes retain their shape original drawing. Characters of this kind are called pictographic or seki - 象形, the Japanese word for Egyptian pictographic writing. There are quite a few signs of this kind among modern hieroglyphs.

Ideographic script "Shizu moji" (指事文字)

"Shizu moji" (指事文字, "pointers") is a type of ideographic or symbolic script. Characters in this category tend to be simple in form and reflect abstract notions of direction or number. For example, 上 means "above" or "top", and 下 means "under" or "bottom". Among modern hieroglyphs, such signs are rare.

Ideographic script "kayi moji" (会意文字)

The hieroglyphs "kayi moji" are called "folded ideograms". As a rule, signs are a combination of a number of pictograms that reflect general meaning. For example, kokuji 峠 (toge, "mountain pass") consists of the characters 山 (mountain), 上 (up), and 下 (down). Another example is the sign 休 (meat "rest") consists of a modified character 人 (man) and 木 (tree). This category is also small.

Phonetic-semantic writing "moji cases" (形声文字)

The hieroglyphs "moji cases" are called "phonetic-semantic" or "phonetic-ideographic" characters. This is the largest category among modern hieroglyphs (up to 90% of them total number). Usually they consist of two components, one of which is responsible for the pronunciation of the character, and the other for the content or semantics. The pronunciation comes from ascending Chinese characters. Often this trace is noticeable in the modern Japanese reading of onyomi. It is worth noting that the semantic component and its content may have changed over a century since its introduction into Japanese or Chinese. Accordingly, mistakes often occur when instead of a phonetic-semantic combination in a hieroglyph, they try to see only a folded ideogram. However, the vidkada - the semantics of the hieroglyph in general - is an even greater mistake.

Derivative letter "tent moji" (転注文字)

This group includes "derivative" or "mutually explaining" hieroglyphs. This category is the most difficult of all, because it does not have a clear definition. This includes signs whose content and application have been expanded. For example, the character 楽 means "music" or "pleasure". In Chinese, depending on the meaning, it is pronounced differently. This is also reflected in the Japanese language, where this sign has different onyomi - hook "music" and cancer "pleasure".

Borrowed letter "kashaku moji" (仮借文字)

This category of "kashaku moji" is called "phonetically borrowed characters". For example, the character 来 in ancient Chinese was an icon for wheat. Its pronunciation was a homophone of the word "arrival", so the hieroglyph began to be used to write this word, without adding a new meaningful element. However, some researchers note that phonetic borrowings occurred as a result of following ideologemes. So the same sign 来 evolved from "wheat" to "arrival", through the meaning of "harvest ripening" or "harvest coming".

Auxiliary signs

The repeat sign (々) in Japanese text means the repetition of the previous character. So, instead of writing two characters in a row (for example, 时时 tokidoki, "sometimes" or 色色 iroiro, "different"), the second character is replaced with a repeat sign and voiced in the same way as a full-fledged character (时々, 色々). The repeat sign can be used in proper names and toponyms, for example in Japanese surname Sasaki (佐々木). The repeat sign is a simplified spelling of the character 同.

Another auxiliary character often used for writing is the ヶ sign (a shortened katakana "ke"). It is pronounced "ka" when used to indicate quantity (for example, in 六ヶ月 rok ka getsu, "six months") or as "ga" in place names, such as in Kanegasaki (金ヶ崎). This symbol is a simplified version of the character 箇.

Dictionaries

To find the desired character in the dictionary, you need to know its key and the number of risks. A Chinese character can be broken down into its simplest components, called keys (more rarely, "radicals"). If there are many keys in the hieroglyph, one main one is taken (it is determined by special rules), after which the desired character is searched in the key section by the number of risks. For example, the character mother (妈) should be looked for in the section of the key (女), which is written with three dashes, among characters consisting of 13 dashes.

Modern Japanese uses 214 classical clefs. In electronic dictionaries, it is possible to search not only by the main key, but by all possible components of the hieroglyph, the number of dashes or reading.

Character Tests in Japan

The main character test in Japan is the Kanji kent test (日本汉字能力検定试験, Nihon kanji noryoku kent shiken). It tests the ability to read, translate and write hieroglyphs. The test is conducted by the Japanese government and is used to test knowledge in schools and universities in Japan. Contains 10 main levels. The most difficult of them tests knowledge of 6000 characters.

For foreigners, there is a simplified Nihongi noryoku shiken test (日本语能力试験, JLPT). It contains 4 levels, the most difficult of which tests knowledge of 1926 hieroglyphs.

Some writing systems have a special sign on which they are based, the hieroglyph. In some languages, it can denote a syllable or sound, in others - words, concepts and morphemes. In the latter case, the name "ideogram" is more common.

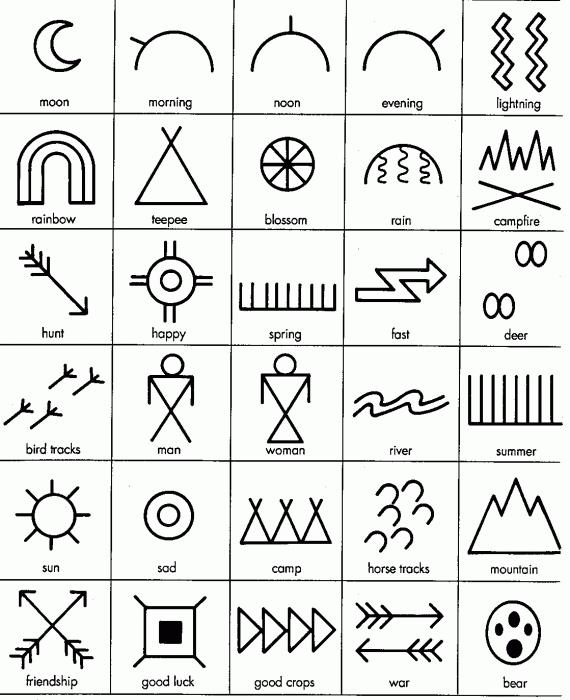

The picture below shows ancient hieroglyphs.

History of hieroglyphs

Translated from Greek the name "hieroglyph" means "sacred letter". For the first time, drawings of a similar plan appeared in Egypt before our era. At first, hieroglyphs denoted letters, that is, they were ideograms, a little later signs appeared that denoted words and syllables. At the same time, it is interesting that only consonants were represented by signs. The name comes from the Greek language, since they were the first to see letters incomprehensible to them on the stones. Judging by the Egyptian chronicles and some myths, the hieroglyphs were invented by the god Thoth. He formed them in order to preserve in writing some of the knowledge gained by the Atlanteans.

An interesting fact is that in Egypt, sign writing appeared already fully formed. Everything scientists and the government did only made it easier. For a long time hieroglyphs and their meaning were incomprehensible to European people. Only in 1822, Chapollion was able to fully study the Egyptian signs on and find their decoding.

In the 50s of the XIX century, some artists working in the style of expressionism and tachisme were very passionate about the East. Thanks to this, a trend associated with the Asian sign system and calligraphy was created. In addition to ancient Egyptian, Chinese and Japanese characters were common.

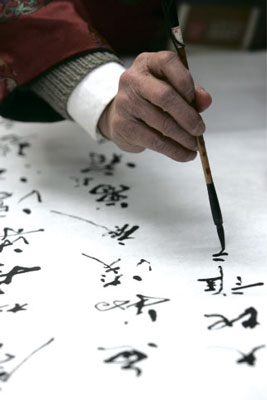

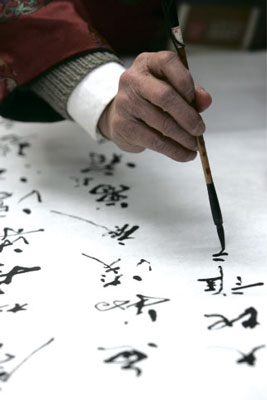

hieroglyphic art

Thanks to the brush (an object with which it is customary to write signs), it is possible to decorate hieroglyphs and give them a more elegant or formal form. The art of beautiful writing is called calligraphy. It is common in Japan, Malaysia, South and North Korea, China, Vietnam. The inhabitants of these countries affectionately call this art "music for the eyes." At the same time, exhibitions and competitions dedicated to beautiful writing are quite often held. ![]()

Hieroglyphs are not only the writing system of some countries, but also a way to express themselves.

Ideographic writing

Ideographic writing in this moment distributed only in China. Initially, it arose in order to simplify writing, to make it more accurate. But in this method, one minus was noticed: such a writing system was not coherent. Because of this, she gradually began to leave the everyday life of people. Now ideographic writing characterizes Chinese hieroglyphs. And their meaning is in many ways similar to the ancient one. The only difference is in the way it is written.

Chinese letter

Chinese writing consists of writing hieroglyphs that represent individual syllables and words, as mentioned above. It was formed in the II century BC. At the moment, there are more than 50 thousand characters, but only 5 thousand are used. In ancient times, such writing was used not only in China, but also in Japan, Korea, Vietnam, having a huge impact on the formation of their cultures. Chinese characters formed the basis of national sign systems. And they are still widely used today.

Origin of Chinese characters

The development of Chinese writing not only affected the whole nation, but also had a huge impact on world art. In the 16th century BC, hieroglyphs were formed. At that time, people wrote on the bones and shells of turtles. Thanks to the excavations of archaeologists and well-preserved remains, it became easier for scientists to make out ancient writing. More than 3,000 signs were found, but only 1,000 were commented on. Modern look this writing acquired only after the complete formation of oral speech. Chinese characters are an ideograph that means a word or a syllable.

Japanese letter

Japanese writing is based on syllabic and alphabetic characters. About 2 thousand hieroglyphs were borrowed from the Chinese peoples for the use of those parts of words that do not change. The rest are written using kana (syllabary). It is divided into two variants: katakana and hiragana. The first is used for words that came from other languages, and the second is purely Japanese. This technique seemed to be the most suitable.

As a rule, Japanese characters in writing are read from left to right, in the case of horizontal writing. Sometimes there is a direction from top to bottom, as well as from right to left.

Origin of Japanese characters

Japanese writing was formed through trial, error and simplification. It was difficult for the people to use only Chinese in documents. Now the formation of language is a matter of constant controversy. Some scholars attribute it to the time of the conquest Japanese islands, while others date back to the Yayoi era. After the introduction of Chinese writing, the oral speech of the nation has undergone dramatic changes.

In the 90s of the XIX century, the government revised all the hieroglyphs, which combined the combination of several types of writing at once, and allowed the use of only 1800 pieces, when in fact there were many more. Now, due to the influence of the American and other Western cultures official speech has practically disappeared, slang acquires more meaning. Due to this, the difference between dialects has decreased.

The emergence of the writing system in Japan

When the Japanese government decided to create a language system, the first characters (this is its main tool) were taken from Chinese writing. This event occurred due to the fact that in ancient times the Chinese often lived, who brought various things, objects, as well as books. It is not known how Japan's own characters developed at that time. Unfortunately, there is practically no data on this subject.

The development of Buddhism in the country had a strong impact on writing. This religion came thanks to the Korean embassy, which arrived in the state and brought various sculptures and texts of the Buddha. For the first time after the full introduction of Chinese writing into the life of Japan, people used foreign words when writing. However, after a few years, discomfort appeared, as the nation's own language was somewhat different and simpler. Problems were also created when writing proper names, where Chinese characters would be used. This has worried the Japanese for a long time. The problem was this: the Chinese language did not have the words and sounds that needed to be recorded in the document.

The idea of splitting special Japanese words into several parts that make sense was completely unfortunate. In this case, the correct reading had to be forgotten. If not to be distracted by the meaning, then these parts of the word had to be highlighted so that the reader understood that he was dealing with words whose meaning could be neglected. This problem existed for a long time, and it had to be solved without going beyond the boundaries of Chinese writing.

Over time, some scholars began to invent special signs with which one could read a text written in Chinese in Japanese. Calligraphy meant that each hieroglyph must be placed in a conditional square in order not to violate the boundaries of the entire letter. The Japanese decided to divide it into several parts, each of which played its own functional role. It was from this time that the characters (Chinese) and their meaning for Japan began to slowly fade into oblivion.

Kukai is the man who (according to legend) created hiragana (the first Japanese script). Thanks to the development in the field of hieroglyphs, special writing systems based on phonetics were created. A little later, by simplifying the form of hieroglyphs, katakana appeared, which became firmly established in use.

Japan borrowed already at that time an ordered script from China because of their territorial proximity. But developing and changing iconic symbols for themselves, people began to invent the first Japanese hieroglyphs. The Japanese could not use the Chinese script in original form, if only because there is no inflection in it. The development of the language did not stop there. When the nation became familiar with other systems (based on hieroglyphs), it took their writing elements and made its language more unique.

The connection of hieroglyphs with the Russian language

Tattoos in the form of Japanese and Chinese characters are very popular now. That is why it is necessary to find out the meaning of hieroglyphs in Russian before stuffing them on your body. It is best to use those that mean "well-being", "happiness", "love" and so on. Before visiting a tattoo artist, it is best to check the meaning in several sources at once.

In Russian-speaking countries, a parody of Asian characters is also popular. Russian hieroglyphs do not exist officially, but only appear on the pages social networks. They are created thanks to the huge imagination of Internet users. Basically, these signs do not carry a special semantic load and exist only for entertainment. Games have also been invented that are based on guessing which word is encrypted in one or another hieroglyph.

In today's article, we will take a closer look.

You will learn:

- How hieroglyphs appeared in Japan

- Why do hieroglyphs have “on” and “kun” readings

- How many hieroglyphs do you need to know

- Why the Japanese will not give up hieroglyphs

- How to read the character "々"

- What order of writing traits should be followed

- And much more!

At the end of the article, you will find copybooks that will help you write some Japanese characters on your own.

Japanese characters and their meaning

For writing, the Japanese use special characters - hieroglyphs, which were borrowed from China. In Japan, hieroglyphs are called so: “Letters (of the dynasty) of Han”, or “Chinese characters” 漢字 (kanji). It is believed that the system of Chinese characters appeared  as early as the 16th century BC. The Japanese language until the 5th century AD. had no written form. This was due to the strong state fragmentation. Japan was a weak state, consisting of many principalities, each of which had its own power, its own dialect. But gradually strong rulers came to power, the unification of principalities began in the country, which led to the adoption of the culture and writing of the most powerful state at that time. It is not known exactly how Chinese writing ended up in Japan, but there is a widespread version that the first hieroglyphs were brought to the country by Buddhist monks. The adaptation of Chinese writing was not easy, because. Japanese language in grammar, vocabulary, phonetics has nothing to do with Chinese. Initially, kanji and Chinese Hanzi were no different from each other. But now there is a difference between them: some hieroglyphs were created in Japan itself - “national hieroglyphs” 国字 (kokuji), some have received a different meaning. And after the Second World War, the writing of many kanji was simplified.

as early as the 16th century BC. The Japanese language until the 5th century AD. had no written form. This was due to the strong state fragmentation. Japan was a weak state, consisting of many principalities, each of which had its own power, its own dialect. But gradually strong rulers came to power, the unification of principalities began in the country, which led to the adoption of the culture and writing of the most powerful state at that time. It is not known exactly how Chinese writing ended up in Japan, but there is a widespread version that the first hieroglyphs were brought to the country by Buddhist monks. The adaptation of Chinese writing was not easy, because. Japanese language in grammar, vocabulary, phonetics has nothing to do with Chinese. Initially, kanji and Chinese Hanzi were no different from each other. But now there is a difference between them: some hieroglyphs were created in Japan itself - “national hieroglyphs” 国字 (kokuji), some have received a different meaning. And after the Second World War, the writing of many kanji was simplified.

Why do Japanese characters need multiple readings?

The Japanese borrowed from Chinese not only hieroglyphs, but also their readings. Having heard the original Chinese reading of a character, the Japanese tried to pronounce it in their own way. This is how the "Chinese" or "on" reading - 音読 (onemi) happened. For example, the Chinese word for water (水) is "shui", taking into account the peculiarities Japanese pronunciation turned into "sui". Some kanji have multiple onomi because they were borrowed from China several times: in different periods and from different areas. But when the Japanese wanted to use characters to write their own words, Chinese readings weren't enough. Therefore, it became necessary to translate the hieroglyphs into Japanese. As well as English word"water" is translated as "みず, mizu", Chinese word"水" was assigned the same meaning - "みず". This is how the “Japanese”, “kun” reading of the hieroglyph appeared - 訓読み, (kunyomi). Some kanji may have several kun at once, or may not have at all. Commonly used Japanese characters can have up to ten different readings. The choice of reading a character depends on many things: context, meaning, combination with other kanji, and even on the place in the sentence. Therefore, often the only the right way to determine where the reading is one-on-one and where the kun is - to learn specific constructions.

How many hieroglyphs are there?

It is almost impossible to answer the question about the total number of hieroglyphs, since their number is truly enormous. Judging by the dictionaries: from 50 to 85 thousand. However, in the computer field, font systems have been released containing encodings for 170-180 thousand characters! It includes all the ancient and modern ideograms ever used throughout the world. In ordinary texts, for example, newspapers or magazines, only a small part of hieroglyphs is used - about 2500 characters. Of course, there are also rare hieroglyphs, mostly technical terms, rare names and surnames. There is a list approved by the Japanese government of "characters for everyday use" ("joyo-kanji"), which contains 2136 characters. It is this number of characters that a graduate of a Japanese school should remember and be able to write.

It is almost impossible to answer the question about the total number of hieroglyphs, since their number is truly enormous. Judging by the dictionaries: from 50 to 85 thousand. However, in the computer field, font systems have been released containing encodings for 170-180 thousand characters! It includes all the ancient and modern ideograms ever used throughout the world. In ordinary texts, for example, newspapers or magazines, only a small part of hieroglyphs is used - about 2500 characters. Of course, there are also rare hieroglyphs, mostly technical terms, rare names and surnames. There is a list approved by the Japanese government of "characters for everyday use" ("joyo-kanji"), which contains 2136 characters. It is this number of characters that a graduate of a Japanese school should remember and be able to write.

How to quickly memorize hieroglyphs?

Why won't the Japanese give up hieroglyphs?

Many learners of Japanese or Chinese often wonder: why does such an inconvenient writing system still exist? Hieroglyphs are classified as ideographic signs, in the outline of which at least a symbolic, but similarity with the depicted object is preserved. For example, the first Chinese characters are images specific items: 木 - "tree", 火 - "fire", etc. The relevance of hieroglyphs today is partly due to the fact that ideographic writing has some advantages over phonographic writing. With the help of the same ideograms, people who speak the same language can communicate different languages, because the ideogram conveys the meaning, not the sound of the word. For example, upon seeing the sign "犬", a Korean, a Chinese and a Japanese will read the character in different ways, but they will all understand that we are talking about the dog. Another advantage is the compactness of the letter, because one character stands for a whole word. But if the Chinese, for example, have no alternative to hieroglyphs, then the Japanese have syllabaries! Will the Japanese give up hieroglyphs in the near future? They won't refuse. Indeed, due to the huge number of homonyms in the Japanese language, the use of hieroglyphs becomes simply necessary. With the same sound, words, depending on their meaning, are written with different hieroglyphs. What can we say about the Japanese mentality, which implies loyalty to traditions and pride in its history. And thanks to the computer, the problem associated with the complex writing of hieroglyphs was resolved. Today, typing Japanese texts can be very fast.

Why is the symbol "々 »?

The character "々" is not a character. As we already know, any ideographic sign has at least one definite phonetic correspondence. The same icon is constantly changing its reading. This symbol is called the repetition sign, and it is needed in order to avoid repeated writing of hieroglyphs. For example, the word "people" consists of two hieroglyphs for "person" - "人人" (hitobito), but this word is written "人々" for simplicity. Although there is no grammatical form in Japanese plural, sometimes it can be formed by repeating kanji, as in our human example:

The character "々" is not a character. As we already know, any ideographic sign has at least one definite phonetic correspondence. The same icon is constantly changing its reading. This symbol is called the repetition sign, and it is needed in order to avoid repeated writing of hieroglyphs. For example, the word "people" consists of two hieroglyphs for "person" - "人人" (hitobito), but this word is written "人々" for simplicity. Although there is no grammatical form in Japanese plural, sometimes it can be formed by repeating kanji, as in our human example:

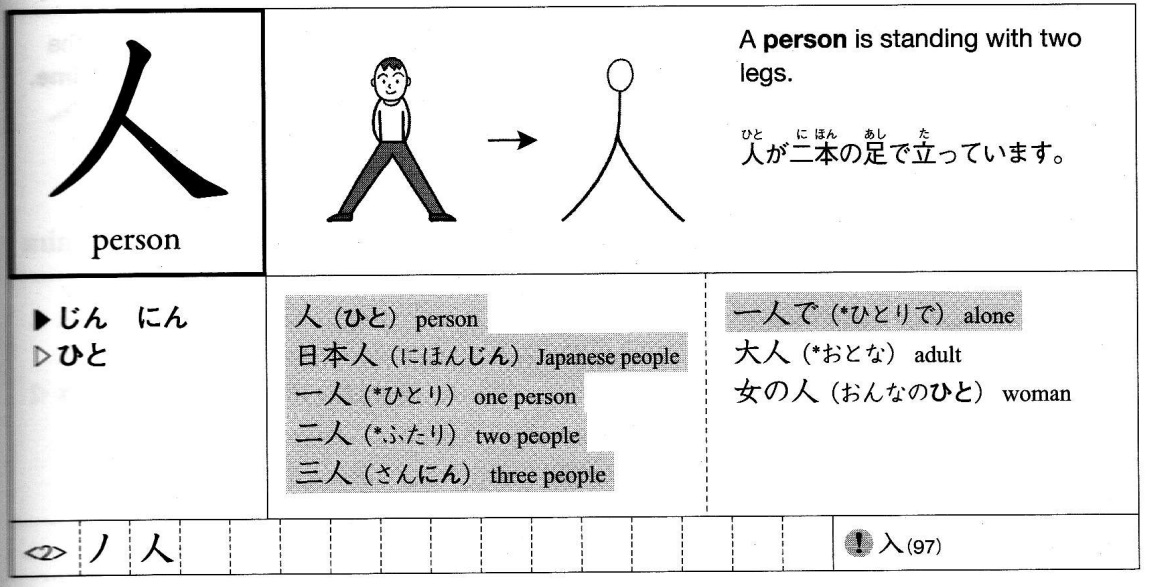

- 人 hito - person; 人々 hitobito - people;

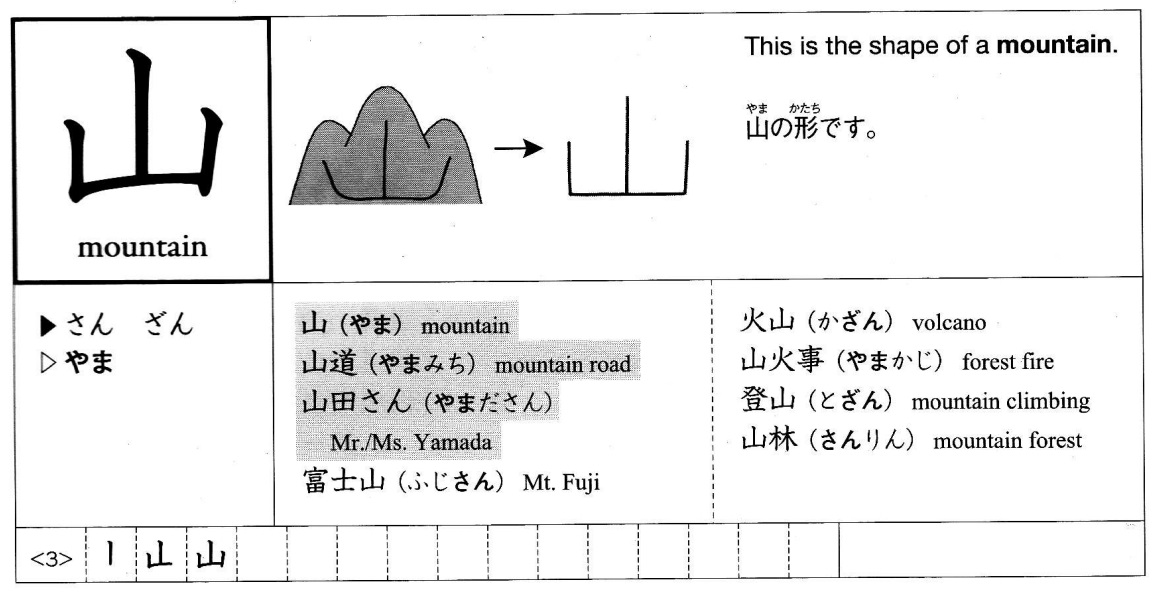

- 山 pit - mountain; 山々 yamayama - mountains;

It also happens that some words change their meaning when doubled:

- 時 currents - time; 時々 tokidoki - sometimes.

The character "々" has many names: the dancing mark 踊り字 (odoriji), the repetition mark 重ね字 (kasaneji), the noma ten ノマ点 (because of its similarity to the katakana characters ノ and マ), and many others.

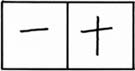

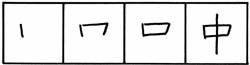

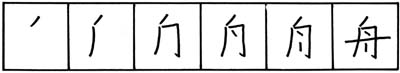

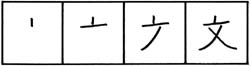

What is the order of writing strokes in hieroglyphs?

Along with Chinese, Japanese characters have a certain sequence of writing strokes. Proper stroke order helps ensure characters are recognizable, even if you write them quickly. The Japanese reduced this order to several rules, which, of course, have exceptions. The most important rule: hieroglyphs are written top to bottom and left to right. Here are some more ground rules:

1. Horizontal lines are written from left to right and are parallel;

2. Vertical lines are written from top to bottom;

3. If the hieroglyph has both vertical and horizontal lines, then the horizontal ones are written first;

4. The vertical crossing the hieroglyph or its element in the center is written last;

5. Horizontal lines passing through the sign are also written last;

6. First, a folding line to the left is written, then a folding line to the right;

At right order hell, the hieroglyph turns out beautiful, and writing it is much easier. All kanji must be the same size. In order for the hieroglyph to be balanced, it must strictly fit into a square of a given size. Now that you know what order of strokes you need to follow, try writing a few simple hieroglyphs that we have already met in this article:

人- person

山 - mountain

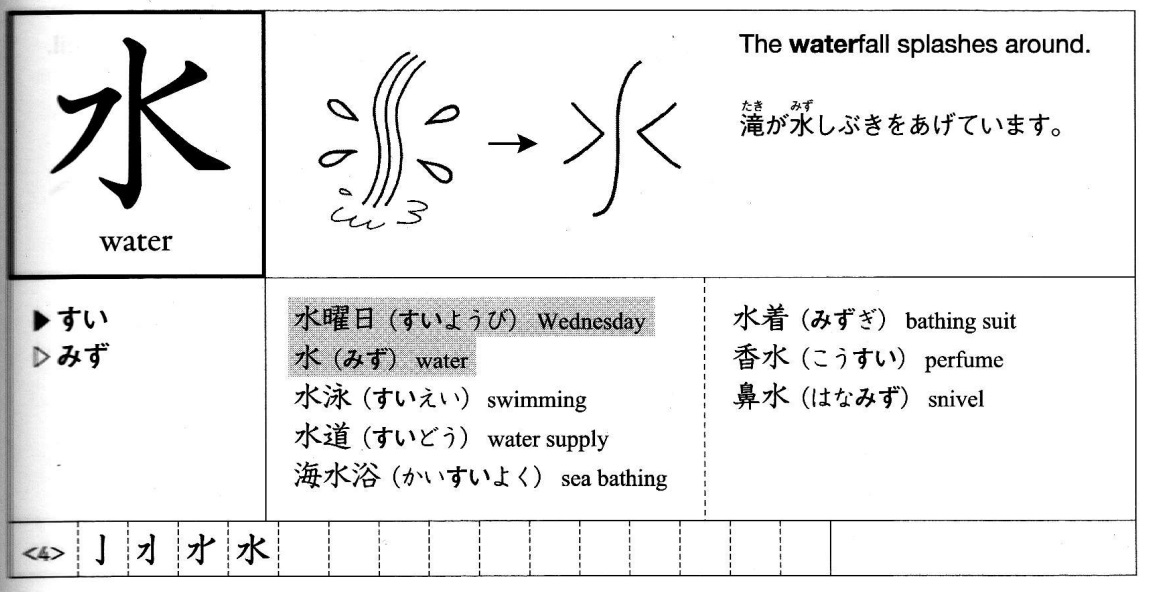

水- water

木-tree

火 - fire

I hope that from this article you have learned something new and interesting for yourself. As homework write the above several times. I think that everyone who is familiar with hieroglyphics has their favorite hieroglyph, one that they immediately remembered or liked. Do you have a favorite hieroglyph? Share in the comments about doing homework, I will also be glad to hear your impressions. Second part .

Want to learn more about hieroglyphs?

Then sign up for a free course on effective learning Japanese characters

You might also be interested three-week training for the effective study of Japanese characters, from which you will learn 30 most popular Japanese characters, 90 common words in Japanese, get a valuable tool for further study of kanji and many other invaluable bonuses.

The number of places on the course is limited. so we would advise you to take the right decision right now. Take the right step towards your dream! Just go to .

Xi Jinping, Chairman of the People's Republic of China, speaking at a symposium dedicated to the 69th anniversary of the victory over the Japanese invaders during the World War, calling on Japan to take a more responsible approach to assessing...

added: 20 Apr 2014

Hieroglyphs - Japanese characters and their meaning

In the 5th-6th century AD, the Japanese borrowed hieroglyphs from China. The addition of its characters to the Chinese signs marked the appearance of ( ) special characters. Modern Japanese characters and their meanings do not differ much from their ancient predecessors.

In addition to symbols, Japanese writing also uses two alphabetic components: hiragana and katakana, and the Latin alphabet along with Arabic numerals.

Story

(漢字) chinese sign reads "Han". As a result, it is rather difficult to determine what part of Chinese characters began to make up Japanese characters, but today it is clear that already in the 5th century, text characters from China became the basis of Japanese writing. Such words, spoken in Chinese and written in Japanese, could be used to match Japanese grammar rules.

At that time, Japan did not have a written form. Manyoshu (Manyoshu) was created to write the native Japanese word. The first example of poetic art ancient literature Japan has become Manyoshu. The meaning of a word expressed in Chinese characters was in the pronunciation, not in the content.

Manyoshu(Manyoshu) The recorded handwritten characters have been converted into Hiragana, a language for women who do not have the opportunity to learn the writing system higher education. The vast majority from the Heian period literary works female writers were written in hiragana.

System Katakana arose in parallel by simplifying the monkstemples values in the monotony of significant factors. These writing systems, katakana and hiragana, formed from Chinese, later formed the basis of Japanese writing, and are collectively known as Kana (provisional name) for Japanese syllables or letters.

The Japanese characters were written in Chinese according to the rules of Japanese grammar in order to make it possible to read the text using diacritics.

In modern Japan, symbols are used to write foundation verbs, nouns, adjectives. At the same time, hiranga is used to write the endings of verbs and adjectives (see. okurigana), particles of words in which it is difficult to remember the meaning. Katakana is also used for recording and onomatopoeia. gayrago(foreign language) .

The Katakana inscription is relatively recent in use. After the Great Patriotic War, the writing of these hieroglyphs had the meaning of meanings (tobacco or ranunculus tobacco - "tobacco", which literally means "grass smoke") or phonetic sounds (or Tempura - a fried product in Portuguese). The last way of writing is called pictograms is called atedzi.

Japanese novelty

First, both China and Japan have largely identical hieroglyphs. Traditionally, Japanese characters and their meaning are used to write Japanese text. However, between hantszy There is not much difference between Chinese and Japanese kanji.

Some characters, being Japanese, have received a slightly different meaning. Also, after World War II, many Japanese words began to be used in simplified writing.

Kokuji (Chinese characters)

Old-style Japanese characters after World War II, in most cases, corresponded to traditional Chinese characters. In 1946, the Japanese government approved the "Japanese kanji jitay hee' (using kanji font table) to simplify the characters of the new styles.

Some of the new character designs matched those used by the Simplified Chinese Character System. The reform of China in writing new hieroglyphs for quick recording introduced unified designations in the form of (abbreviated words, ryakudzi) using the borrowing of some forms.

However, in some cases, it is still allowed to use old style in the form of hieroglyphs (spelling, Seiji Ozawa). People also use old hieroglyphs for simplified spelling. Although their number is very limited to personal correspondence.

In theory, any of the Chinese characters in Japanese text can be used, but in practice it shows that many Chinese characters are not currently used in Japanese.

Read symbols

Depending on the method of deciphering the hieroglyph in Japanese, it can have different meanings and be used to interpret different words or morphemes. But from the reader's point of view, this means that a symbol can have one or more meanings. The meaning of a hieroglyph for the reader depends on the context, content and interaction with other hieroglyphs, and sometimes on the position in the sentence.

Reading is divided into two types: "Sino-Japanese" and "Japanese".

Onyomi

Onyomi- reading Chinese characters. Some meanings of onyomi characters, because they are borrowed from Chinese, have different interpretations.

Kokuji or Japanese who invented their character usually do not have onyomi, but there are exceptions. For example, the hieroglyph japanese character love or the hieroglyph "work" has the character kunemi (hataraku), but he also onyomi, however, the meaning of the word "breast cancer" is the only onyomi.

Kunemi

Kunemi is a Japanese reading that is based on the Japanese native pronunciation of the words. (Yamato Kotoba, - " loud words”), to which Chinese characters were selected according to their meaning. In other words, kunemi are Chinese characters translated into Japanese.

Video: Writing the Japanese character World