Charles of Valois is the son of Catherine de Medici. Mistresses of old times

I will touch lightly on people who did not directly belong to this family, but who are not at all alien to it. The people who surrounded the first representative of this family to ascend the French royal throne - Catherine de Medici.

I remind you that my notes are just a wandering through the pages of Wikipedia - not claiming anything other than the sole purpose - to collect accessible portraits of the Medici, those in whom their blood flowed as closely as possible, and those who were in lifetime communication with them through was in different circumstances.

The history of this genus, in the person of its individual representatives, is so eventful and interesting that even a superficial acquaintance already ignites the blood and awakens the imagination... You don’t need to read any novels - check out real stories lives... A lot of passion and a lot of actions, dictated not only by political and economic benefits, but also by the vivid feelings of people who are accustomed to achieving what they want at any cost...

In general - rich in characters Italian history, the maximum human individuality was revealed in them - as in good deeds, and in the evil ones. And do not divide its heroes by black and white flowers, because their abilities in any matter reached the maximum possible flowering, and one and the same person was capable of the most tender and devoted love, and of dirty betrayal...

1. Henry II(March 31, 1519, Saint-Germain Palace - July 10, 1559, Paris) - King of France from March 31, 1547, second son of Francis 1 from his marriage to Claude of France, daughter of Louis 12, from the Angoulême line of the Valois dynasty. Husband of Catherine de Medici. 25th King of France.

2. Gabriel I de Montgomery, senor de Ducy d'Exmes and de Lorges, count (1530, Ducie - 1574) - Norman aristocrat, involuntary killer of King Henry II. The duel between Montgomery and the king was the last in the history of European knightly tournaments. The absurd death of Henry was the formal reason for their ban. Catherine hated him and in the end managed to send him to the chopping block.

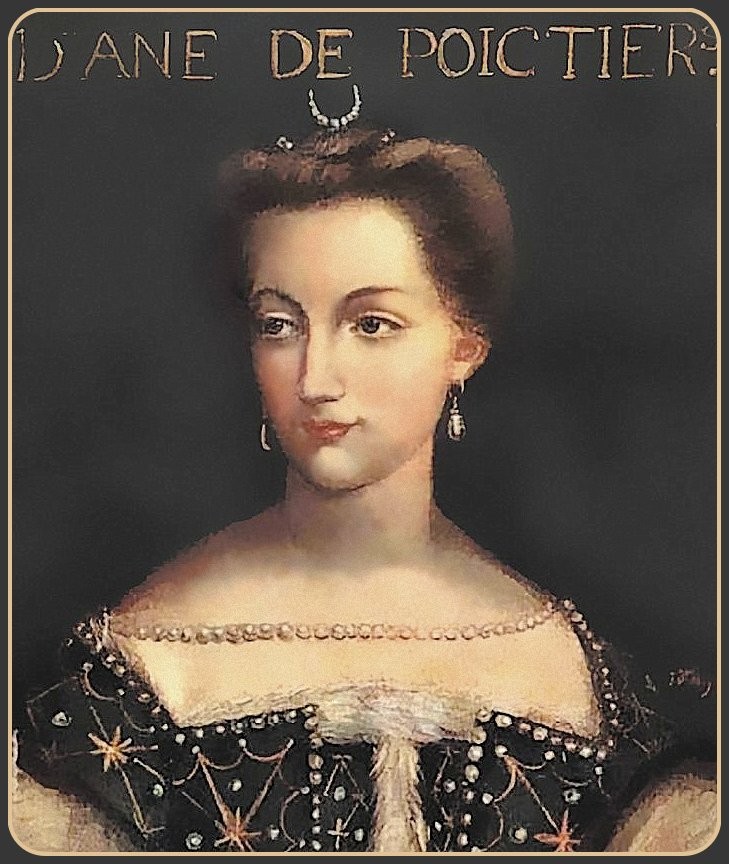

3. Diane de Poitiers(1499 - 1566) - beloved and official favorite of King Henry II.

4. Diana of France(July 25, 1538 - January 11, 1619) - illegitimate (legitimized) daughter of the French king Henry II. She bore three ducal titles - duchess of Chatellerault, Etampes and Angoulême. She was the illegitimate daughter of the Dauphin Henry (the future King Henry II) and Philippa Duci from Piedmont. Diana was raised by King Henry's favorite, Diana de Poitiers, and this gave reason to believe that the girl was the king's daughter from her. This is what Brant thought, for example. Diana received a proper upbringing: she knew several languages (Spanish, Italian and Latin), played several musical instruments and danced well.

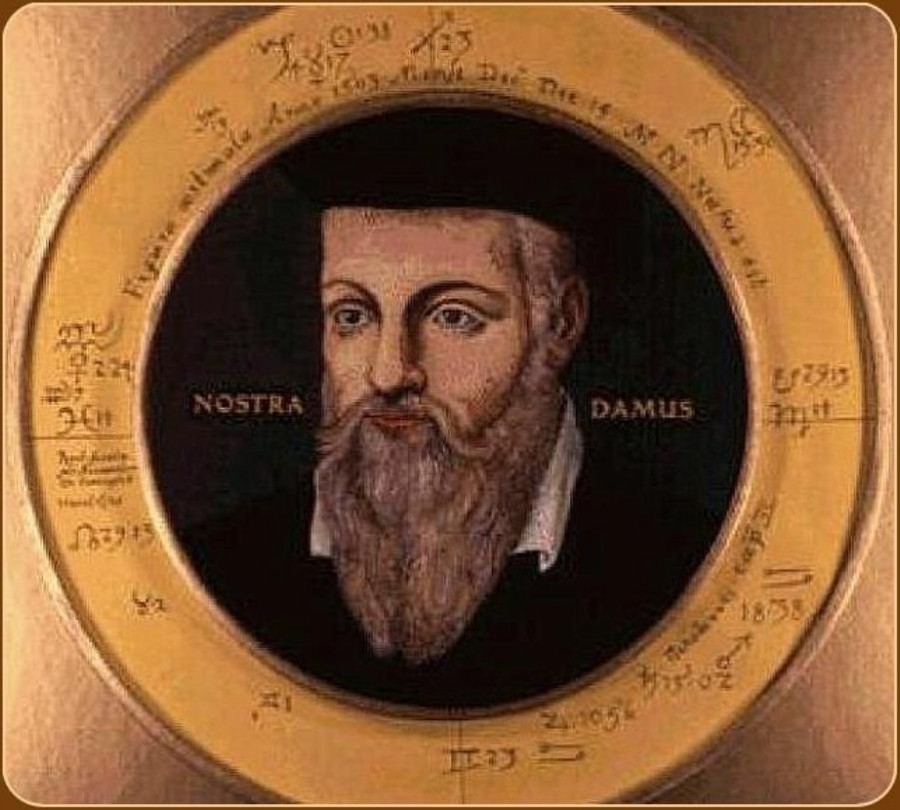

5. Michel de Nostredame, also known as Nostradamus (December 14, 1503 – July 2, 1566) was a French astrologer, physician, pharmacist and alchemist, famous for his prophecies.

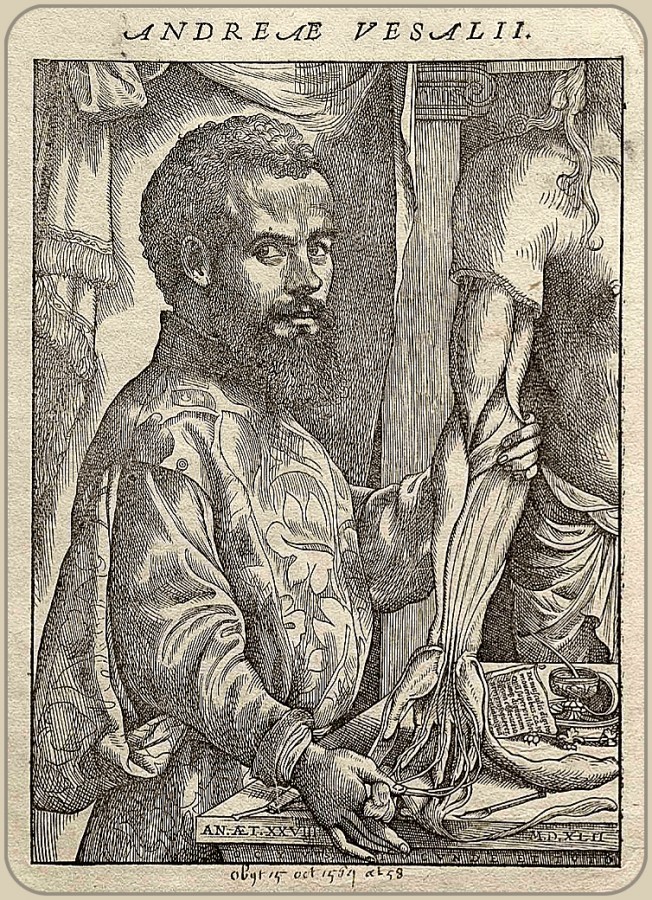

6. Andreas Vesalius(December 31, 1514, Brussels, Seventeen Provinces - October 15, 1564, Zakynthos, Venetian Republic) - doctor and anatomist, physician to Charles V, then Philip II. A younger contemporary of Paracelsus, the founder of scientific anatomy. Tried to save the wounded man at the tournament of Henry II.

7. Francis II(January 19, 1544, Fontainebleau Palace, France - December 5, 1560, Orleans, France) - King of France from July 10, 1559, King Consort of Scotland from April 24, 1558. From the Valois dynasty. Son of Henry II and Catherine de Medici.

8. Maria I(née Mary Stewart, 8 December 1542 - 8 February 1587) - Queen of Scots from infancy, effectively reigning from 1561 until her deposition in 1567, as well as Queen of France in 1559-1560 (as the wife of King Francis II) and pretender to the English throne. The eldest son of Henry II, named after his grandfather, Francis I. On April 24, 1558, he married the young Queen of Scotland, Mary Stuart (he was the first of her three husbands). The agreement on this marriage was concluded on January 27, 1548 (when the bride and groom were 4 and 6 years old, respectively), and for the next 10 years, Maria was raised at the French court. Francis I loved his wife to the point of adoration.

9. Pierre de Ronsard(between September 1 and September 11, 1524, La Possoniere castle, Vendomois - December 27, 1585, Saint-Côme Abbey, near Tours) - famous French poet XVI century. He headed the Pleiades association, which preached the enrichment of national poetry by the study of Greek and Roman literature.

He served as a page to Francis I, then at the Scottish court.

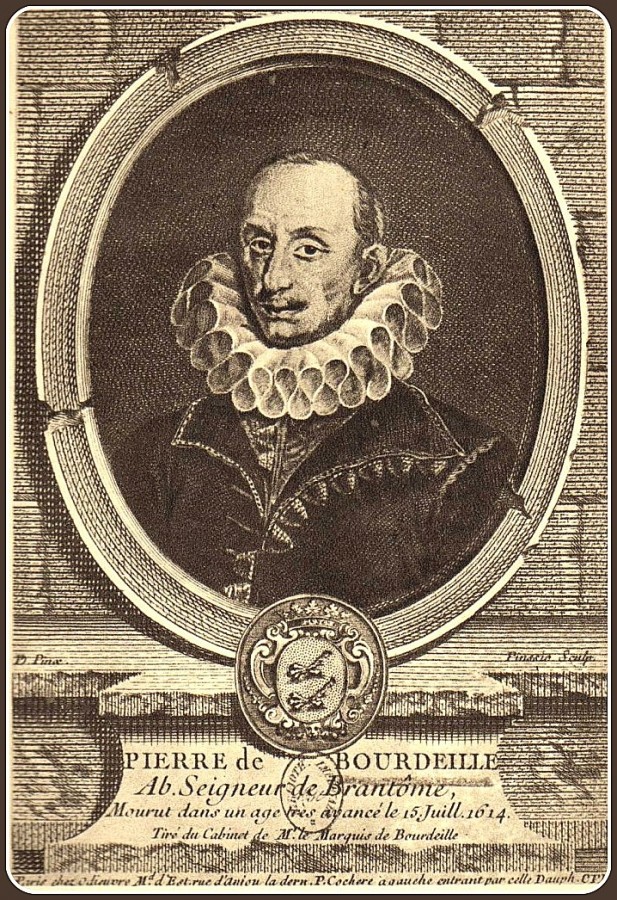

10. Pierre de Bourdeil, lord of Brantôme(c. 1540 - July 15, 1614) - chronicler of court life during the times of Catherine de Medici, one of the most widely read French authors Renaissance. Brantome's memoirs are written vividly and are full of anecdotes. His frankness regarding privacy court celebrities later, in Victorian era, seemed scandalous. The author's reluctance to evaluate even the most dissolute, by the standards of later times, behavior of his heroes allowed him to be accused not only of frivolity, but also of cynicism.

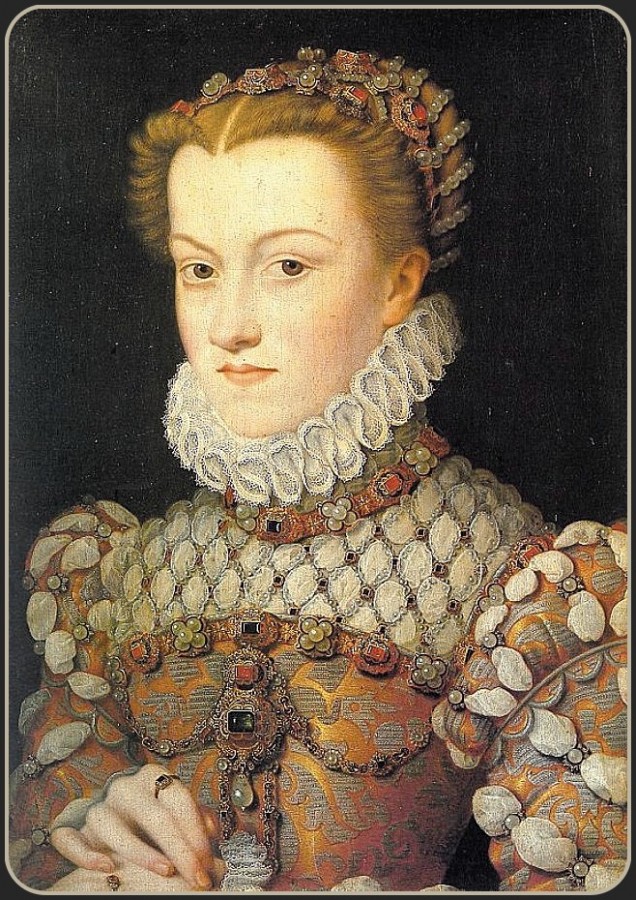

11. Elizabeth of Valois(April 2, 1545, Fontainebleau - October 3, 1568, Aranjuez) - French princess and queen of Spain, third wife of King Philip II of Spain.

Elizabeth of Valois was eldest daughter King of France Henry II of the Valois dynasty and his wife Catherine de Medici. Although she was engaged to the Spanish Infante Don Carlos, fate decreed otherwise, and at the end of the many years of war between France and Spain, which ended in 1559 with the signing of the peace treaty of Cateau Cambresis, she married the Spanish King Philip II, which was one of the terms of this agreement. Elisabeth Valois for a short time transformed from a French princess into a Spanish queen, whose intelligence, gentleness and beauty were highly valued throughout Europe. Elizabeth carried out the duties associated with her royal office in an exemplary manner.

Elizabeth inherited black hair, dark eyes and high intelligence from her Italian mother. But unlike her mother, Elizabeth had a softer character and more tact in her behavior; she was also distinguished by great piety. Catherine was surprised to discover in her daughter those qualities that she lacked, and over time they established a close, trusting relationship, which, after Elizabeth married Philip II, continued in the form of lively correspondence

Elizabeth died in 1568 due to another unsuccessful birth.

12. Philip II May 21, 1527 - September 13, 1598) - King of Spain from the Habsburg dynasty. The son and heir of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (aka Charles (Carlos) I, King of Castile and Aragon), Philip was King of Naples and Sicily from 1554, and from 1556, after his father’s abdication of the throne, became King of Spain and the Netherlands and the owner of all overseas possessions of Spain. In 1580 he also annexed Portugal and became its king. Husband of Elizabeth Valois.

When his mother died, Philip was not even twelve. In the serene environment of his childhood, he developed a deep love for nature. Subsequently, throughout his life, trips to nature, fishing and hunting became a desirable and best release for him after heavy workloads. From childhood, Philip was distinguished by deep religiosity. He also loved music and attached great importance so that you can include your children in it. Philip's letters, now over fifty, from Lisbon, where he had to spend two years without his young children, show him loving father: He worries about the health of the kids, is interested in his son’s first tooth and is worried about him getting a picture book to color. Perhaps this was due to the warmth that he received in abundance in his childhood years.

13. Isabella Clara Eugenia, Isabel Clara Eugenia (August 12, 1566, Segovia - December 1, 1633, Brussels) - Spanish infanta, ruler of the Spanish Netherlands. The parents of Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia were King Philip II of Spain and Elizabeth of Valois.

14. Catalina Michaela of Austria(and October 10, 1567, Madrid - November 6, 1597, Turin) - Spanish infanta and Duchess of Savoy, wife of Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy. Catalina Micaela was the youngest daughter of King Philip II of Spain and his third wife Elizabeth of Valois. She was named after her maternal grandmother Catherine de Medici and St. Michaela. Catalina Michaela married Duke Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy on March 18, 1585 in Zaragoza and left the Spanish court. Despite the separation, she maintained a lively correspondence with her father and other family members until his death. Catalina gave birth to 10 children and was most family life on demolitions. She died at the age of 29 on October 6, 1597 in Turin from complications caused by premature birth a year after the birth of her last child, Thomas Franz of Savoy. Thomas Franz was the grandfather of Eugene Franz of Savoy, better known as Prince Eugene of Savoy. Although Catalina suffered the same fate as her mother, she nonetheless fulfilled her dynastic duty and gave birth to an heir to the throne for the House of Savoy.

15. Claude Valois, or Claude of France(November 12, 1547, Fontainebleau - February 21, 1575, Nancy) - the second daughter of Henry II and Catherine de Medici. This modest, lame, hunchbacked princess was the beloved daughter of Catherine de Medici. Having married at the age of 11, at the age of 27 Claude died in childbirth. She had nine children.

16. Charles III(February 18, 1543, Nancy - May 14, 1608, ibid.) - Duke of Lorraine from 1545 until his death. As a descendant of Gerhard I, he was supposed to be Charles II, but Lorraine historians, wanting to attribute Carolingian kinship to the Dukes of Lorraine, included Charles I of the Carolingian dynasty in the numbering. Eldest son of Duke of Lorraine François I and Christina of Denmark. Spouse Claude Valois.

17. Christina of Lorraine(16 August 1565 - 19 December 1637) - Grand Duchess of Tuscany. Favorite granddaughter of Catherine de' Medici. Her parents were Duke Charles III and his wife Claude Valois, daughter of Catherine de' Medici. She received her name in honor of her paternal grandmother, Christina of Denmark. After her mother's death in 1575, Christina lived at the court of her grandmother Catherine de' Medici in Paris. In 1587, Francesco I (Grand Duke of Tuscany) died without a male heir, and his brother Ferdinand immediately proclaimed himself the new Duke. In search of a marriage option that would help him maintain political independence, Ferdinand settled on distant relative- Christina. Catherine de' Medici facilitated this marriage. Ferdinand and Christina had nine children.

18. Louis III of Orleans(February 3, 1549, Fontainebleau, France - October 24, 1550, Mantes-la-Jolie, France) - Duke of Orleans, second son and fourth child in the family of Henry II, King of France and Catherine de' Medici. Brother of three kings of France - Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III. Like his older brother, he was given to be raised by Diane de Poitiers. According to some reports, they wanted to make him the heir of the Duke of Urbino, but the plans were not implemented. After baptism, he died in the city of Mantes-la-Jolie on October 24, 1550.

In the background of the painting are the last children of Catherine de Medici - twins Victoria(lived for 1 month and Zhanna(born dead). The birth was very difficult and doctors forbade Catherine to have children. This was in 1556.

19. Charles IX, Charles Maximilien(June 27, 1550 - May 30, 1574) - before the last king France from the Valois dynasty, from December 5, 1560. Third son of King Henry II and Catherine de Medici. His mother was his regent until August 17, 1563. Charles's reign was marked by numerous Wars of Religion and St. Bartholomew's Night - the notorious mass extermination of the Huguenots. At the age of 20 (November 26, 1570), he married Elizabeth of Austria. The king was interested in literature. Poems from his pen are known, as well as “Treatise on the Royal Hunt,” first published in 1625.

20. Elizabeth of Austria(July 5, 1554, Vienna - January 22, 1592, Vienna) - Queen of France, wife of King Charles IX of France. Elizabeth was the fifth child and second daughter of Emperor Maximilian II and his cousin, the Spanish Infanta Maria, daughter of Charles V and sister of King Philip II of Spain . On November 26, 1570, she married King Charles IX of France, who died in 1574. They had one daughter who lived only 5 years. She was considered one of the most beautiful princesses in Europe, with red-golden hair, a lovely face and a charming smile. But she was not just beautiful: the chronicler and poet Brantôme described Elizabeth this way: she was “one of the best, meekest, smartest and most virtuous queens who ever reigned from time immemorial.” Contemporaries agree on her intelligence, shyness, virtue, sympathetic heart and, above all, sincere piety. Widowed at the age of twenty, Elizabeth returned to Austria. In 1576, she retired to the monastery of the Clarissas, which she herself founded.

21. Maria Touchet(1549, Orleans - March 28, 1638, Paris) - official favorite of King Charles IX, mother of Catherine Henriette d'Entragues (favourite of the French king Henry IV after the death of Gabrielle d'Estrées in 1599, and mother of his two illegitimate children), and Charles de Valois (April 28, 1573 - September 24, 1650) - Count of Auvergne (1589-1650), Duke of Angoulême (1619-1650), Count de Ponthieu (1619-1650), Peer of France - illegitimate son Charles IX. Daughter of Lieutenant Jean Touchet, who served as assistant to the governor at the Orleans Court and his wife Marie Mathy. In the fall of 1566, at a ball (according to other sources, at a hunt) in Orleans, she met the future king of France, Charles IX, and fell in love with him at first sight. Maria was distinguished by her beauty, education, and meekness; According to her memoirs, a contemporary was “ round face, a beautiful cut, lively eyes, a well-proportioned nose, a small mouth, a delightfully defined lower part of the face.” Karl was fascinated by the young Flemish woman and took her to Paris. Here Maria was first a maid younger sister King Princess Margaret, then worked at the Louvre, and after St. Bartholomew's Night, as a result of which she was almost killed, she lived in Fayet Castle. Despite her status as the official favorite, Marie Touchet cheated on Karl.

22. Henry III of Valois(September 19, 1551, Fontainebleau - August 2, 1589, Saint-Cloud) - fourth son of Henry II, King of France and Catherine de Medici, Duke of Angoulême (1551-1574), Duke of Orleans (1560-1574), Duke of Anjou (1566-1574) , Duke of Bourbon (1566-1574), Duke of Auvergne (1569-1574), King of Poland and Grand Duke Lithuanian from February 21, 1573 to June 18, 1574 (formally until May 12, 1575), from May 30, 1574 the last king of France from the Valois dynasty.

Alexander-Eduard-Henry was a cheerful, friendly and smart child. The education of the young prince was carried out famous people of his time - François Carnavalet and Bishop Jacques Amiot, famous for his translations of Aristotle. In his youth, he read a lot, willingly held conversations about literature, took rhetoric lessons, danced and fenced well, and knew how to charm with his charm and elegance. Fluent in Italian (which he often spoke with his mother), he read the works of Machiavelli. Like all nobles, he early began to engage in various physical exercise and later, during military campaigns, he showed good skill in military affairs. Henry’s personality and behavior sharply distinguished him in the French court. And later, upon arrival in Poland, they called culture shock from the local population. In 1573, the Venetian ambassador to Paris, Morisoni, wrote about the prince’s luxurious clothes, his almost “ladylike delicacy,” and his earrings in each ear. Catherine herself, who loved Henry more than her other children, dreamed of leaving him the royal crown. She called him “my everything” and “my little eagle”, signed her letters to him “your dearly loving mother” and saw in him character traits that reminded her of her ancestors, the Medici. Heinrich was her favorite as a child, and later became her confidant.

23. Maria of Cleves, Countess de Beaufort (1553 - October 30, 1574, Paris) - the first wife of the second Prince of Condé. Someone else's bride, with whom Henry III fell in love and with whom he dreamed of marrying. The 21-year-old is “a child from the provinces with a pure heart, fresh cheeks, a slender figure, a healthy body and a heartfelt smile.” Catherine was horrified by her son's desire; Maria did not belong to the highest nobility at all. Through her efforts, her son’s plans were upset - Maria married someone else. Having ascended the throne, Henry III hoped to dissolve Mary's marriage and marry her. However, Maria soon died from postpartum complications. Since the king’s affection for Mary was no secret to anyone, no one wanted to take the liberty of informing him of the princess’s death. A note with a message was placed in a bundle of the king's daily correspondence. After reading it, Heinrich fainted, and it took a quarter of an hour to revive him. After a week of hysterics, the king fell into melancholy, dressed in mourning, retired to the chapel several times a day and often made pilgrimages.

24. Louise of Lorraine-Vaudemont(April 30, 1553 - January 29, 1601) - representative of the House of Lorraine, wife of Henry III of Valois and French queen from 1575 to 1589. Catherine de Medici was very surprised when Henry announced that he intended to marry Louise de Vaudemont. Henry III, unwilling to lose independence and fearing to become the husband of an overly domineering woman, he wanted to marry a tender and meek girl who would be his devoted assistant. He was too tired of the power of his own mother and did not want to find her in a wife. A confidant, Philippe Cheverny, writes in his “Memoirs”: From the words of the king, I understood that he wanted to choose a woman of his nationality, beautiful and pleasant. He needs her to love her and have children. He is not going to go to others, as his predecessors did. His heart was almost already inclined to Louise de Vaudemont. Having revealed his feelings, the king honored me and asked me to speak with the queen and achieve her positive answer.

Louise did not even imagine the possibility of such a marriage. The King of France left a deep imprint on her heart when she saw him as the Duke of Anjou. But she understood that she could not count on such a brilliant match. And when her stepmother entered her bedroom in the morning, she was very surprised, but, as Antoine Malet reports: ... her surprise increased even more when her stepmother curtsied three times in front of her before turning and greeting her as the Queen of France; the girl thought it was a joke and apologized for being in bed so late, but then the father entered the room and, sitting down by his daughter’s bed, said that the king of France wanted to take her as his wife... After the tragedy that happened on 1 August 1589, when Henry III was assassinated, Queen Louise would never again lift her mourning, becoming the "White Queen". According to royal etiquette, only white clothes are to be worn during mourning...

25. Hercule Francois (Francis) de Valois(March 18, 1555 - June 10, 1584), Duke of Alençon, then Duke of Anjou, was a French prince, the youngest son of King Henry II of France and Catherine de Medici, the only one of four brothers who never became king.

A charming child, he unfortunately suffered from smallpox at the age of 8, which left scars on his face. His pockmarked face and slightly crooked spine did not really correspond to the name given at birth - Hercule, that is, “Hercules”. At his confirmation, he changed his name to François in honor of his brother Francis II, King of France.

Before the accession to the throne of his brother, the Duke of Anjou (Henry III), he bore the title of Duke of Alençon, and then was called the Duke of Anjou. He stood at the head of political groups hostile to the French kings. Thus, he participated in a conspiracy against Charles IX, but was forgiven because he betrayed his comrades Count J.B. de La Mole and Count Annibal de Coconas, who were executed in 1574. He helped the Protestants, then took part in the war against them, opposed Philip II at the head of the rebellious Flemings, was proclaimed Duke of Brabant and Count of Flanders, but was soon expelled by the Flemings themselves. He died on June 10, 1584 from tuberculosis.

26. Marguerite de Valois(May 14, 1553, Saint-Germain Palace, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France - March 27, 1615, Paris, France), also known as "Queen Margot" was a French princess, daughter of King Henry II and Catherine de' Medici. In 1572-1599, she was the wife of Henry de Bourbon, King of Navarre, who, under the name of Henry IV, took the French throne. From an early age, the girl was distinguished by her charm, independent disposition and sharp mind, and in the spirit of the Renaissance received a good education: knew Latin, ancient Greek, Italian, Spanish, studied philosophy and literature, and she herself had a good command of the pen. Nobody except her brother, King Charles, called her Margot.

27. Henry (Henri) I of Lorraine, nicknamed Marked or Chopped (December 31, 1550 - December 23, 1588, Castle of Blois), 3rd Duke of Guise (1563 - 1588), Prince de Joinville, Peer of France (1563 - 1588), Knight of the Order of the Holy Spirit (1579) . French military and statesman during the Wars of Religion in France. Head of the Catholic League. The eldest son of Francois of Lorraine, Duke of Guise. Guise was one of the instigators of St. Bartholomew's Night and, in order to avenge the death of his father, took upon himself the murder of Admiral Coligny. In the skirmish of Dormans in 1575 he received a wound, as a result of which he was given the nickname Chopped. He had whirlwind romance with Margarita, but for political reasons their marriage was impossible. Apparently, Guise and Margarita retained feelings for each other until the end of their lives, which is confirmed by the queen’s secret correspondence.

28. Henry (Henri) IV the Great(Henry of Navarre, Henry of Bourbon, December 13, 1553, Pau, Bearn - killed May 14, 1610, Paris) - leader of the Huguenots at the end of the Wars of Religion in France, king of Navarre from 1572 (as Henry III), king of France from 1589 (formally - from 1594), founder of the French royal dynasty Bourbons. First marriage - Margarita de Valois (no children), second marriage - Maria Medici (5 children).

29. Maria de Medici(April 26, 1575, Florence - July 3, 1642, Cologne) - Queen of France, second wife of Henry IV of Bourbon, mother of Louis XIII.

So - the circle is closed.

From the first French queen from the Medici family, whose children were the last kings of France from the Valois dynasty, we come to the second French queen from the same Medici family, whose children belonged to the next, brilliant dynasty of kings of France - the Bourbon dynasty.

Catherine's parents - Lorenzo II, di Piero, de' Medici, Duke of Urbino (September 12, 1492 - May 4, 1519) and Madeleine de la Tour, Countess of Auvergne (c. 1500 - April 28, 1519) were married as a sign of the alliance between King Francis I of France and by Pope Leo X, Lorenzo's uncle, against Emperor Maximilian I of Habsburg. The young couple was very happy about the birth of their daughter; according to the chronicler, they “were as pleased as if it were a son.” But, unfortunately, their joy was not destined to last long: Catherine’s parents died in the first month of her life - her mother on the 15th day after giving birth (at the age of nineteen), and her father outlived his wife by only six days, leaving the newborn as an inheritance Duchy of Urbino and County of Auvergne. After this, the newborn was cared for by her grandmother Alfonsina Orsini until her death in 1520. Catherine was raised by her aunt, Clarissa Strozzi, along with her children, whom Catherine loved as siblings all her life. One of them, Pietro Strozzi, rose to the rank of marshal's baton in the French service. The death of Pope Leo X in 1521 led to a break in Medici power on the Holy See until Cardinal Giulio de' Medici became Clement VII in 1523. In 1527, the Medici in Florence were overthrown, and Catherine became a hostage - she was imprisoned in a monastery. Clement was forced to recognize and crown Charles of Habsburg as Holy Roman Emperor in exchange for his help in recapturing Florence and freeing the young duchess.  Pope Clement VII In October 1529, the troops of Charles V besieged Florence. During the siege, there were calls and threats to kill Catherine. There were other ideas regarding the fate of Catherine: they proposed placing the girl on the wall between two battlements under artillery fire, or giving her to the soldiers to be mocked. Although the city resisted the siege, on August 12, 1530, famine and plague forced Florence to surrender. Clement met Catherine in Rome with tears in his eyes. It was then that he began to search for a groom for her, considering many options, but when in 1531 the French king Francis I proposed the candidacy of his second son Henry, Clement immediately jumped at the chance: the young Duke of Orleans was the most profitable match for his niece Catherine . Fourteen-year-old Catherine, leaving Florence on September 1, 1533, said goodbye to Italy forever. Catherine could not be called beautiful. On her arrival in Rome, one Venetian ambassador described her as "red-haired, short and thin, but with expressive eyes" - typical appearance Medici family. But Catherine was able to impress the refined French court, spoiled by luxury, by turning to the help of one of the most famous Florentine craftsmen, who made shoes for the young bride. high heels. Her appearance at the French court caused a sensation. The wedding, which took place in Marseilles on October 28, 1533, was a major event marked by extravagance and the distribution of gifts. Europe has not seen such a gathering of the highest clergy for a long time. Pope Clement VII himself attended the ceremony, accompanied by many cardinals. “The wedding of Henry Valois and Catherine lasted thirty-four days,” Honore de Balzac said about the events of distant times. “...The Pope demanded that both of these teenagers become actually husband and wife on the very day of the celebration - he was so afraid of the various tricks and tricks that were in use at that time.” He wanted to make sure that the union was now indissoluble and Francis I could not refer to “non-consummation of marriage” in order to return Catherine to him. However, the king himself announced his decision to be present at the wedding night of the young newlyweds - this fact is confirmed by several testimonies. After the wedding, 34 days of continuous feasts and balls followed. On wedding feast Italian chefs first introduced the French court to a new dessert made from fruit and ice - this was the first ice cream.

Pope Clement VII In October 1529, the troops of Charles V besieged Florence. During the siege, there were calls and threats to kill Catherine. There were other ideas regarding the fate of Catherine: they proposed placing the girl on the wall between two battlements under artillery fire, or giving her to the soldiers to be mocked. Although the city resisted the siege, on August 12, 1530, famine and plague forced Florence to surrender. Clement met Catherine in Rome with tears in his eyes. It was then that he began to search for a groom for her, considering many options, but when in 1531 the French king Francis I proposed the candidacy of his second son Henry, Clement immediately jumped at the chance: the young Duke of Orleans was the most profitable match for his niece Catherine . Fourteen-year-old Catherine, leaving Florence on September 1, 1533, said goodbye to Italy forever. Catherine could not be called beautiful. On her arrival in Rome, one Venetian ambassador described her as "red-haired, short and thin, but with expressive eyes" - typical appearance Medici family. But Catherine was able to impress the refined French court, spoiled by luxury, by turning to the help of one of the most famous Florentine craftsmen, who made shoes for the young bride. high heels. Her appearance at the French court caused a sensation. The wedding, which took place in Marseilles on October 28, 1533, was a major event marked by extravagance and the distribution of gifts. Europe has not seen such a gathering of the highest clergy for a long time. Pope Clement VII himself attended the ceremony, accompanied by many cardinals. “The wedding of Henry Valois and Catherine lasted thirty-four days,” Honore de Balzac said about the events of distant times. “...The Pope demanded that both of these teenagers become actually husband and wife on the very day of the celebration - he was so afraid of the various tricks and tricks that were in use at that time.” He wanted to make sure that the union was now indissoluble and Francis I could not refer to “non-consummation of marriage” in order to return Catherine to him. However, the king himself announced his decision to be present at the wedding night of the young newlyweds - this fact is confirmed by several testimonies. After the wedding, 34 days of continuous feasts and balls followed. On wedding feast Italian chefs first introduced the French court to a new dessert made from fruit and ice - this was the first ice cream. ![]() On September 25, 1534, Clement VII died unexpectedly. Paul III, who replaced him, dissolved the alliance with France and refused to pay Catherine's dowry. Catherine's political value suddenly disappeared, thereby worsening her position in an unfamiliar country. King Francis complained that “the girl came to me completely naked.” Catherine, born in merchant Florence, where her parents were not concerned with giving their offspring a comprehensive education, had a very difficult time at the sophisticated French court. She felt like an ignorant person who did not know how to elegantly construct phrases and made many mistakes in her letters. We must not forget that French was not native to her, she spoke with an accent, and although she spoke quite clearly, the ladies of the court contemptuously pretended that they did not understand her well. Catherine was isolated from society and suffered from loneliness and hostility from the French, who arrogantly called her “Italian” and “merchant’s wife.” In 1536, the eighteen-year-old Dauphin Francis unexpectedly died and Catherine's husband became heir to the French throne. Now Catherine had to worry about the future of the throne. The death of his brother-in-law marked the beginning of speculation about the involvement of the Florentine woman in his poisoning for the quick accession of “Catherine the Poisoner” to the French throne: the heir, who drank a glass of ice water in Lyon after a game of ball, suddenly died. According to the official version, the Dauphin died of a cold, nevertheless the courtier, the Italian Count of Montecuccoli, served him, heated gambling, a bowl with cold water, was executed.

On September 25, 1534, Clement VII died unexpectedly. Paul III, who replaced him, dissolved the alliance with France and refused to pay Catherine's dowry. Catherine's political value suddenly disappeared, thereby worsening her position in an unfamiliar country. King Francis complained that “the girl came to me completely naked.” Catherine, born in merchant Florence, where her parents were not concerned with giving their offspring a comprehensive education, had a very difficult time at the sophisticated French court. She felt like an ignorant person who did not know how to elegantly construct phrases and made many mistakes in her letters. We must not forget that French was not native to her, she spoke with an accent, and although she spoke quite clearly, the ladies of the court contemptuously pretended that they did not understand her well. Catherine was isolated from society and suffered from loneliness and hostility from the French, who arrogantly called her “Italian” and “merchant’s wife.” In 1536, the eighteen-year-old Dauphin Francis unexpectedly died and Catherine's husband became heir to the French throne. Now Catherine had to worry about the future of the throne. The death of his brother-in-law marked the beginning of speculation about the involvement of the Florentine woman in his poisoning for the quick accession of “Catherine the Poisoner” to the French throne: the heir, who drank a glass of ice water in Lyon after a game of ball, suddenly died. According to the official version, the Dauphin died of a cold, nevertheless the courtier, the Italian Count of Montecuccoli, served him, heated gambling, a bowl with cold water, was executed. ![]() The birth of an illegitimate child to her husband in 1537 confirmed rumors about Catherine’s infertility. Many advised the king to annul the marriage. Under pressure from her husband, who wanted to consolidate her position with the birth of an heir, Catherine was treated for a long time and in vain by various magicians and healers with one single goal - to get pregnant. Every possible means was used to achieve successful conception, including drinking mule urine and wearing cow dung and deer antlers on the lower abdomen. Finally, on January 20, 1544, Catherine gave birth to a son. The boy was named Francis in honor of his grandfather, reigning king(he even shed tears of happiness when he learned about this). After her first pregnancy, Catherine seemed to no longer have problems conceiving. With the birth of several more heirs, Catherine strengthened her position at the French court. The long-term future of the Valois dynasty seemed assured. The sudden miraculous cure for infertility is associated with the famous doctor, alchemist, astrologer and fortuneteller Michel Nostradamus, one of the few members of Catherine’s close circle of confidants. Heinrich often played with children and was even present at their births. In 1556, during her next birth, surgeons saved Catherine from death by breaking off the legs of one of the twins, Jeanne, who lay dead in her mother’s womb for six hours. However, the second girl, Victoria, was destined to live only six weeks. In connection with this birth, which was very difficult and almost caused the death of Catherine, doctors advised the royal couple not to think about having new children anymore; after this advice, Henry stopped visiting his wife’s bedroom, spending everything free time with his favorite Diane de Poitiers

The birth of an illegitimate child to her husband in 1537 confirmed rumors about Catherine’s infertility. Many advised the king to annul the marriage. Under pressure from her husband, who wanted to consolidate her position with the birth of an heir, Catherine was treated for a long time and in vain by various magicians and healers with one single goal - to get pregnant. Every possible means was used to achieve successful conception, including drinking mule urine and wearing cow dung and deer antlers on the lower abdomen. Finally, on January 20, 1544, Catherine gave birth to a son. The boy was named Francis in honor of his grandfather, reigning king(he even shed tears of happiness when he learned about this). After her first pregnancy, Catherine seemed to no longer have problems conceiving. With the birth of several more heirs, Catherine strengthened her position at the French court. The long-term future of the Valois dynasty seemed assured. The sudden miraculous cure for infertility is associated with the famous doctor, alchemist, astrologer and fortuneteller Michel Nostradamus, one of the few members of Catherine’s close circle of confidants. Heinrich often played with children and was even present at their births. In 1556, during her next birth, surgeons saved Catherine from death by breaking off the legs of one of the twins, Jeanne, who lay dead in her mother’s womb for six hours. However, the second girl, Victoria, was destined to live only six weeks. In connection with this birth, which was very difficult and almost caused the death of Catherine, doctors advised the royal couple not to think about having new children anymore; after this advice, Henry stopped visiting his wife’s bedroom, spending everything free time with his favorite Diane de Poitiers  Diane de Poitiers Back in 1538, the thirty-nine-year-old beautiful widow Diana captivated the nineteen-year-old heir to the throne, Henry of Orleans, which over time allowed her to become an extremely influential person, as well as (in the opinion of many) the true ruler of the state. In 1547, Henry spent a third of every day with Diana. Having become king, he gave his beloved the castle of Chenonceau. When King Francis I died and Henry II ascended the throne, it was not Catherine de Medici, his wife, who became the real queen, but Diana. Even at the coronation she took an honorary public place, while Catherine was at a distant podium. This showed everyone that Diana had completely taken the place of Catherine, who, in turn, was forced to endure her husband’s beloved. She, like a real Medici, even managed to overcome herself, humble her pride, and win over her husband’s influential favorite. Diana was very pleased that Henry was married to a woman who preferred not to interfere and turned a blind eye to everything. Having become Diana's faithful knight, Henry wore the colors of the mistress of his heart: white and black - right up to the last breath and decorated his rings and clothes with the double monogram “DH” (Diana - Henry). On March 31, 1547, Francis I died and Henry II ascended the throne. Catherine became Queen of France. The coronation took place in the Basilica of Saint-Denis in June 1549. During the reign of her husband, Catherine had only minimal influence on the administration of the kingdom. Even in Henry's absence, her power was very limited. In early April 1559, Henry II signed the peace treaty of Cateau-Cambresis, ending the long wars between France, Italy and England. The agreement was strengthened by the engagement of Catherine and Henry's fourteen-year-old daughter, Princess Elizabeth, to thirty-two-year-old Philip II of Spain. Defying the predictions of the astrologer Luca Gorico and Nostradamus, who advised him to abstain from tournaments, Henry decided to participate in the competition. On June 30 or July 1, 1559, he fought in a duel with the lieutenant of his Scots guard, Earl Gabriel de Montgomery. Montgomery's split spear passed through the slot of the king's helmet. Through Henry's eye, the tree entered the brain, mortally wounding the monarch. The king was taken to the castle de Tournel, where the remaining fragments of the ill-fated spear were removed from his face. The best doctors in the kingdom fought for Henry's life. Catherine was at her husband's bedside all the time, and Diana did not appear, probably for fear of being sent away by the queen. From time to time, Henry even felt well enough to dictate letters and listen to music, but he soon became blind and lost his speech. Diana was removed during the agony of Henry II. She was forced to return the Crown Jewels in accordance with the inventory. The Duchess was frightened: she asked Catherine's forgiveness and handed her her property and her life. The Queen Mother was generous. She limited herself to forbidding Diana and one of her daughters, the Duchess de Bouillon, from coming to court; but not the other - to the Duchess d'Aumale - the daughter-in-law of the Duke of Guise. Perhaps, in order to preserve the inheritance of the Duke d'Aumale, the Guises did not confiscate her fortune from Diana, as she herself once did in relation to the Duchess d'Etampes. Catherine was content with which forced the former favorite to sell Chenonceau to her, giving her her possession of Chaumont in return. Everyone was surprised by the queen’s generosity: her jealousy and contempt for Diana during her husband’s life were well known; Catherine was afraid of the influence of Diana’s powerful family alliances. Therefore, she limited herself to the resignation of the duchess. her supporters: thus, the keeper of the seals, Cardinal Jean Bertrand, was forced to give up his place to Chancellor Olivier. Later, the queen would be able to express her contempt: going to the siege of Rouen in September 1562, she would pass by Anet and “would not see Madame de Valantinois or enter her house.”

Diane de Poitiers Back in 1538, the thirty-nine-year-old beautiful widow Diana captivated the nineteen-year-old heir to the throne, Henry of Orleans, which over time allowed her to become an extremely influential person, as well as (in the opinion of many) the true ruler of the state. In 1547, Henry spent a third of every day with Diana. Having become king, he gave his beloved the castle of Chenonceau. When King Francis I died and Henry II ascended the throne, it was not Catherine de Medici, his wife, who became the real queen, but Diana. Even at the coronation she took an honorary public place, while Catherine was at a distant podium. This showed everyone that Diana had completely taken the place of Catherine, who, in turn, was forced to endure her husband’s beloved. She, like a real Medici, even managed to overcome herself, humble her pride, and win over her husband’s influential favorite. Diana was very pleased that Henry was married to a woman who preferred not to interfere and turned a blind eye to everything. Having become Diana's faithful knight, Henry wore the colors of the mistress of his heart: white and black - right up to the last breath and decorated his rings and clothes with the double monogram “DH” (Diana - Henry). On March 31, 1547, Francis I died and Henry II ascended the throne. Catherine became Queen of France. The coronation took place in the Basilica of Saint-Denis in June 1549. During the reign of her husband, Catherine had only minimal influence on the administration of the kingdom. Even in Henry's absence, her power was very limited. In early April 1559, Henry II signed the peace treaty of Cateau-Cambresis, ending the long wars between France, Italy and England. The agreement was strengthened by the engagement of Catherine and Henry's fourteen-year-old daughter, Princess Elizabeth, to thirty-two-year-old Philip II of Spain. Defying the predictions of the astrologer Luca Gorico and Nostradamus, who advised him to abstain from tournaments, Henry decided to participate in the competition. On June 30 or July 1, 1559, he fought in a duel with the lieutenant of his Scots guard, Earl Gabriel de Montgomery. Montgomery's split spear passed through the slot of the king's helmet. Through Henry's eye, the tree entered the brain, mortally wounding the monarch. The king was taken to the castle de Tournel, where the remaining fragments of the ill-fated spear were removed from his face. The best doctors in the kingdom fought for Henry's life. Catherine was at her husband's bedside all the time, and Diana did not appear, probably for fear of being sent away by the queen. From time to time, Henry even felt well enough to dictate letters and listen to music, but he soon became blind and lost his speech. Diana was removed during the agony of Henry II. She was forced to return the Crown Jewels in accordance with the inventory. The Duchess was frightened: she asked Catherine's forgiveness and handed her her property and her life. The Queen Mother was generous. She limited herself to forbidding Diana and one of her daughters, the Duchess de Bouillon, from coming to court; but not the other - to the Duchess d'Aumale - the daughter-in-law of the Duke of Guise. Perhaps, in order to preserve the inheritance of the Duke d'Aumale, the Guises did not confiscate her fortune from Diana, as she herself once did in relation to the Duchess d'Etampes. Catherine was content with which forced the former favorite to sell Chenonceau to her, giving her her possession of Chaumont in return. Everyone was surprised by the queen’s generosity: her jealousy and contempt for Diana during her husband’s life were well known; Catherine was afraid of the influence of Diana’s powerful family alliances. Therefore, she limited herself to the resignation of the duchess. her supporters: thus, the keeper of the seals, Cardinal Jean Bertrand, was forced to give up his place to Chancellor Olivier. Later, the queen would be able to express her contempt: going to the siege of Rouen in September 1562, she would pass by Anet and “would not see Madame de Valantinois or enter her house.”  Henry II died on July 10, 1559. From that day on, Catherine chose as her emblem a broken spear with the inscription “Lacrymae hinc, hinc dolor” (“from this all my tears and my pain”) and until the end of her days she wore black clothes as a sign of mourning. She was the first to wear black mourning. Before this, in medieval France, mourning was white. Despite everything, Catherine adored her husband. “I loved him so much...” she wrote to her daughter Elizabeth after Henry’s death. Catherine de Medici mourned for her husband for thirty years and went down in French history under the name “The Black Queen.” Her eldest son, fifteen-year-old Francis II, became the King of France. Catherine took up state affairs, made political decisions, and exercised control over the Royal Council. However, Catherine never ruled the entire country, which was in chaos and on the brink of civil war. Many parts of France were virtually dominated by local nobles. Complex tasks, which Catherine found herself in front of, were confusing and to some extent difficult for her to understand. She called on religious leaders on both sides to engage in dialogue to resolve their doctrinal differences. Despite her optimism, the "Conference of Poissy" ended in failure on October 13, 1561, dissolving itself without the queen's permission. Catherine's point of view on religious issues was naive because she saw the religious schism from a political perspective. “She underestimated the power of religious conviction, imagining that all would be well if only she could persuade both parties to agree.” “The king’s health is very uncertain,” the Tuscan ambassador reported to his court, “and Nostradamus, in his predictions for this month, says that the king’s death will occur before the new year.” And so it happened: on December 5, 1560, Francis II died. The death was blamed on the cupbearer, who allegedly mixed poison into the intoxicating drink. However, historians are still arguing about the reliability of this fact. But it is definitely established that even when Francis was the Dauphin (in 1555), an attempt was made to poison him. The scenario is traditional: a luxurious feast, a cupbearer... And if not for the healing talent of Nostradamus, Francis would have died as the Dauphin.

Henry II died on July 10, 1559. From that day on, Catherine chose as her emblem a broken spear with the inscription “Lacrymae hinc, hinc dolor” (“from this all my tears and my pain”) and until the end of her days she wore black clothes as a sign of mourning. She was the first to wear black mourning. Before this, in medieval France, mourning was white. Despite everything, Catherine adored her husband. “I loved him so much...” she wrote to her daughter Elizabeth after Henry’s death. Catherine de Medici mourned for her husband for thirty years and went down in French history under the name “The Black Queen.” Her eldest son, fifteen-year-old Francis II, became the King of France. Catherine took up state affairs, made political decisions, and exercised control over the Royal Council. However, Catherine never ruled the entire country, which was in chaos and on the brink of civil war. Many parts of France were virtually dominated by local nobles. Complex tasks, which Catherine found herself in front of, were confusing and to some extent difficult for her to understand. She called on religious leaders on both sides to engage in dialogue to resolve their doctrinal differences. Despite her optimism, the "Conference of Poissy" ended in failure on October 13, 1561, dissolving itself without the queen's permission. Catherine's point of view on religious issues was naive because she saw the religious schism from a political perspective. “She underestimated the power of religious conviction, imagining that all would be well if only she could persuade both parties to agree.” “The king’s health is very uncertain,” the Tuscan ambassador reported to his court, “and Nostradamus, in his predictions for this month, says that the king’s death will occur before the new year.” And so it happened: on December 5, 1560, Francis II died. The death was blamed on the cupbearer, who allegedly mixed poison into the intoxicating drink. However, historians are still arguing about the reliability of this fact. But it is definitely established that even when Francis was the Dauphin (in 1555), an attempt was made to poison him. The scenario is traditional: a luxurious feast, a cupbearer... And if not for the healing talent of Nostradamus, Francis would have died as the Dauphin.  Catherine declared herself regent: the new king, Charles IX, was only ten years old. This sullen and cruel teenager had a morbid addiction to blood - he killed animals for his own pleasure, cut the throats of his dogs, and strangled birds. He was never able to govern the state on his own and showed minimal interest in state affairs. Karl was also prone to hysterics, which over time turned into outbursts of rage. He suffered from shortness of breath - a sign of tuberculosis, which ultimately brought him to the grave. Arrogant, contemptuous and sickly, Karl grew into an intolerable tyrant. His relationship with his mother left much to be desired, although he could not yet do without her advice. Repeated attempts to poison this monarch, some authors note, ended in nothing. Charles reigned for fourteen years (all this time Nostradamus was listed as the court physician) and died in 1574. Through dynastic marriages, Catherine sought to expand and strengthen the interests of the House of Valois. In 1570, Charles was married to the daughter of Emperor Maximilian II, Elizabeth. Catherine tried to marry one of her younger sons to Elizabeth of England. She did not forget about her youngest daughter Margaret, whom she saw as the bride of the again widowed Philip II of Spain. However, soon Catherine had plans to unite the Bourbons and Valois through the marriage of Margaret and Henry of Navarre. Margaret, however, encouraged the attention of Henry de Guise, son of the late Duke François de Guise. When Catherine and Karl found out about this, Margarita received a good thrashing. The escaped Henry of Guise hastily married Catherine of Cleves, which restored the favor of the French court towards him. Perhaps it was this incident that caused the split between Catherine and Giza. Between 1571 and 1573, Catherine persistently tried to win over the mother of Henry of Navarre, Queen Jeanne. When, in another letter, Catherine expressed a desire to see her children, while promising not to harm them, Jeanne d'Albret replied: “Forgive me if, reading this, I want to laugh, because you want to free me from a fear that I never had. I never thought that, as they say, you eat small children.” Ultimately, Joan agreed to a marriage between her son Henry and Margaret, with the condition that Henry would continue to adhere to the Huguenot faith. Shortly after arriving in Paris to prepare for the wedding, forty-four-year-old Jeanne fell ill and died. The Huguenots were quick to accuse Catherine of killing Jeanne with poisoned gloves. The wedding of Henry of Navarre and Margaret of Valois took place on August 18, 1572 at Notre Dame Cathedral.

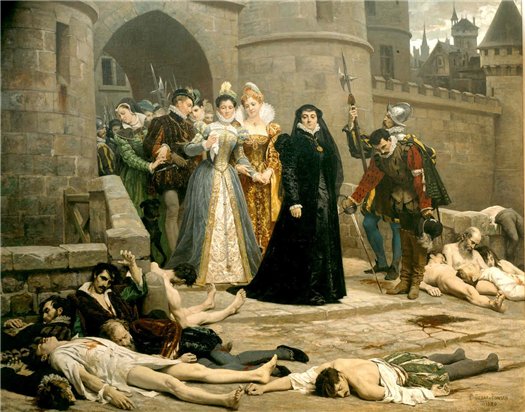

Catherine declared herself regent: the new king, Charles IX, was only ten years old. This sullen and cruel teenager had a morbid addiction to blood - he killed animals for his own pleasure, cut the throats of his dogs, and strangled birds. He was never able to govern the state on his own and showed minimal interest in state affairs. Karl was also prone to hysterics, which over time turned into outbursts of rage. He suffered from shortness of breath - a sign of tuberculosis, which ultimately brought him to the grave. Arrogant, contemptuous and sickly, Karl grew into an intolerable tyrant. His relationship with his mother left much to be desired, although he could not yet do without her advice. Repeated attempts to poison this monarch, some authors note, ended in nothing. Charles reigned for fourteen years (all this time Nostradamus was listed as the court physician) and died in 1574. Through dynastic marriages, Catherine sought to expand and strengthen the interests of the House of Valois. In 1570, Charles was married to the daughter of Emperor Maximilian II, Elizabeth. Catherine tried to marry one of her younger sons to Elizabeth of England. She did not forget about her youngest daughter Margaret, whom she saw as the bride of the again widowed Philip II of Spain. However, soon Catherine had plans to unite the Bourbons and Valois through the marriage of Margaret and Henry of Navarre. Margaret, however, encouraged the attention of Henry de Guise, son of the late Duke François de Guise. When Catherine and Karl found out about this, Margarita received a good thrashing. The escaped Henry of Guise hastily married Catherine of Cleves, which restored the favor of the French court towards him. Perhaps it was this incident that caused the split between Catherine and Giza. Between 1571 and 1573, Catherine persistently tried to win over the mother of Henry of Navarre, Queen Jeanne. When, in another letter, Catherine expressed a desire to see her children, while promising not to harm them, Jeanne d'Albret replied: “Forgive me if, reading this, I want to laugh, because you want to free me from a fear that I never had. I never thought that, as they say, you eat small children.” Ultimately, Joan agreed to a marriage between her son Henry and Margaret, with the condition that Henry would continue to adhere to the Huguenot faith. Shortly after arriving in Paris to prepare for the wedding, forty-four-year-old Jeanne fell ill and died. The Huguenots were quick to accuse Catherine of killing Jeanne with poisoned gloves. The wedding of Henry of Navarre and Margaret of Valois took place on August 18, 1572 at Notre Dame Cathedral.  Three days later, one of the Huguenot leaders, Admiral Gaspard Coligny, on his way from the Louvre, was wounded in the arm by a shot from the window of a nearby building. The smoking arch was left in the window, but the shooter managed to escape. Coligny was carried to his apartment, where surgeon Ambroise Paré removed the bullet from his elbow and amputated one of his fingers. Catherine was said to have reacted to this incident without emotion. She visited Coligny and tearfully promised to find and punish her attacker. Many historians blamed Catherine for the attack on Coligny. Others point to the de Guise family or to a Spanish-papal conspiracy that tried to end Coligny's influence over the king. The name of Catherine de Medici is associated with one of the bloodiest events in the history of France - St. Bartholomew's Night. The massacre, which began two days later, tarnished Catherine's reputation indelibly. There is no doubt that she was behind the decision on August 23, when Charles IX ordered: “Then kill them all, kill them all!” The train of thought was clear, Catherine and her Italian advisers (Albert de Gondi, Lodovico Gonzaga, Marquis de Villars) expected a Huguenot uprising after the assassination attempt on Coligny, so they decided to strike first and destroy the Huguenot leaders who came to Paris for the wedding of Margaret of Valois and Henry of Navarre . The St. Bartholomew massacre began in the first hours of August 24, 1572. The king's guards burst into Coligny's bedroom, killed him and threw his body out of the window. At the same time, the sound of the church bell was a conventional sign for the beginning of the murders of the Huguenot leaders, most of whom died in their own beds. The king's newly minted son-in-law, Henry of Navarre, was faced with a choice between death, life imprisonment and conversion to Catholicism. He decided to become a Catholic, after which he was asked to stay in the room for his own safety. All the Huguenots inside and outside the Louvre were killed, and those who managed to escape into the street were shot by the royal riflemen who were waiting for them. The Parisian massacre continued for almost a week, spreading across many provinces of France, where indiscriminate killings continued. According to historian Jules Michelet, "Bartholomew's Night was not a night, but a whole season." This massacre delighted Catholic Europe, and Catherine enjoyed the praise. On September 29, when Henry of Bourbon knelt before the altar like a good Catholic, she turned to the ambassadors and laughed. From this time on, the “black legend” of Catherine, the evil Italian queen, began. An interesting point: Karl once publicly accused his mother of being to blame for organizing St. Bartholomew’s Night, and, moreover, declared that he would now rule himself without her help. The scandal ended with a dinner with reconciliation, but it was after this dinner that Karl finally fell ill and fell ill.

Three days later, one of the Huguenot leaders, Admiral Gaspard Coligny, on his way from the Louvre, was wounded in the arm by a shot from the window of a nearby building. The smoking arch was left in the window, but the shooter managed to escape. Coligny was carried to his apartment, where surgeon Ambroise Paré removed the bullet from his elbow and amputated one of his fingers. Catherine was said to have reacted to this incident without emotion. She visited Coligny and tearfully promised to find and punish her attacker. Many historians blamed Catherine for the attack on Coligny. Others point to the de Guise family or to a Spanish-papal conspiracy that tried to end Coligny's influence over the king. The name of Catherine de Medici is associated with one of the bloodiest events in the history of France - St. Bartholomew's Night. The massacre, which began two days later, tarnished Catherine's reputation indelibly. There is no doubt that she was behind the decision on August 23, when Charles IX ordered: “Then kill them all, kill them all!” The train of thought was clear, Catherine and her Italian advisers (Albert de Gondi, Lodovico Gonzaga, Marquis de Villars) expected a Huguenot uprising after the assassination attempt on Coligny, so they decided to strike first and destroy the Huguenot leaders who came to Paris for the wedding of Margaret of Valois and Henry of Navarre . The St. Bartholomew massacre began in the first hours of August 24, 1572. The king's guards burst into Coligny's bedroom, killed him and threw his body out of the window. At the same time, the sound of the church bell was a conventional sign for the beginning of the murders of the Huguenot leaders, most of whom died in their own beds. The king's newly minted son-in-law, Henry of Navarre, was faced with a choice between death, life imprisonment and conversion to Catholicism. He decided to become a Catholic, after which he was asked to stay in the room for his own safety. All the Huguenots inside and outside the Louvre were killed, and those who managed to escape into the street were shot by the royal riflemen who were waiting for them. The Parisian massacre continued for almost a week, spreading across many provinces of France, where indiscriminate killings continued. According to historian Jules Michelet, "Bartholomew's Night was not a night, but a whole season." This massacre delighted Catholic Europe, and Catherine enjoyed the praise. On September 29, when Henry of Bourbon knelt before the altar like a good Catholic, she turned to the ambassadors and laughed. From this time on, the “black legend” of Catherine, the evil Italian queen, began. An interesting point: Karl once publicly accused his mother of being to blame for organizing St. Bartholomew’s Night, and, moreover, declared that he would now rule himself without her help. The scandal ended with a dinner with reconciliation, but it was after this dinner that Karl finally fell ill and fell ill.  With the death of twenty-three-year-old Charles IX, Catherine faced a new crisis. With dying words Catherine's dying son were: “Oh, my mother...” The day before his death, he appointed his mother as regent, since his brother, the heir to the French throne, the Duke of Anjou, was in Poland, becoming its king. In her letter to Henry, Catherine wrote: “I am heartbroken... My only consolation is to see you here soon, as your kingdom requires and in good health, because if I lose you too, I will bury myself alive with you.” Henry was Catherine's beloved son. Unlike his brothers, he took the throne at an adult age. He was also the healthiest of all, although he also had weak lungs and suffered from constant fatigue. Catherine could not control Henry the way she did with Francis and Charles. Her role during Henry's reign was that of a state executive and traveling diplomat. In addition, there were persistent rumors that Heinrich did not let a single handsome young man through, and this plunged his mother into despair. During the reign of Henry III civil wars in France often descended into anarchy, supported by the struggle for power between the high nobility of France on the one hand and the clergy on the other. A new destabilizing component in the kingdom was the youngest son of Catherine de Medici - Francois, Duke of Alençon. He plotted to seize the throne while Henry was in Poland and later continued to disturb the peace in the kingdom, using every opportunity. The brothers hated each other. Since Henry had no children, Francois was the legal heir to the throne. Once Catherine had to lecture him for six hours about his, Francois, behavior. But the ambitions of the Duke of Alençon (later of Anjou) brought him closer to misfortune. His ill-equipped campaign in the Netherlands in January 1583 ended with the destruction of his army in Antwerp. Antwerp was the end military career Francois. Catherine de Medici wrote in a letter to him: “... it would have been better for you to die in your youth. Then you would not have caused the death of so many brave noble people.” Another blow befell him when Elizabeth I officially broke off her engagement to him after the Antwerp massacre. On June 10, 1584, François died of exhaustion after failures in the Netherlands. The day after her son’s death, Catherine wrote: “I am so unhappy, living long enough, seeing so many people die before me, although I understand that God’s desire must be obeyed, that He owns everything and what He lends us only so far.” as long as He loves the children He gives us.” Death of himself youngest son Catherine became a real disaster for her dynastic plans. Henry III had no children, and it seemed unlikely that he would ever have any. According to the Salic Law, the former Huguenot Henry of Bourbon, King of Navarre, became the heir to the French crown.

With the death of twenty-three-year-old Charles IX, Catherine faced a new crisis. With dying words Catherine's dying son were: “Oh, my mother...” The day before his death, he appointed his mother as regent, since his brother, the heir to the French throne, the Duke of Anjou, was in Poland, becoming its king. In her letter to Henry, Catherine wrote: “I am heartbroken... My only consolation is to see you here soon, as your kingdom requires and in good health, because if I lose you too, I will bury myself alive with you.” Henry was Catherine's beloved son. Unlike his brothers, he took the throne at an adult age. He was also the healthiest of all, although he also had weak lungs and suffered from constant fatigue. Catherine could not control Henry the way she did with Francis and Charles. Her role during Henry's reign was that of a state executive and traveling diplomat. In addition, there were persistent rumors that Heinrich did not let a single handsome young man through, and this plunged his mother into despair. During the reign of Henry III civil wars in France often descended into anarchy, supported by the struggle for power between the high nobility of France on the one hand and the clergy on the other. A new destabilizing component in the kingdom was the youngest son of Catherine de Medici - Francois, Duke of Alençon. He plotted to seize the throne while Henry was in Poland and later continued to disturb the peace in the kingdom, using every opportunity. The brothers hated each other. Since Henry had no children, Francois was the legal heir to the throne. Once Catherine had to lecture him for six hours about his, Francois, behavior. But the ambitions of the Duke of Alençon (later of Anjou) brought him closer to misfortune. His ill-equipped campaign in the Netherlands in January 1583 ended with the destruction of his army in Antwerp. Antwerp was the end military career Francois. Catherine de Medici wrote in a letter to him: “... it would have been better for you to die in your youth. Then you would not have caused the death of so many brave noble people.” Another blow befell him when Elizabeth I officially broke off her engagement to him after the Antwerp massacre. On June 10, 1584, François died of exhaustion after failures in the Netherlands. The day after her son’s death, Catherine wrote: “I am so unhappy, living long enough, seeing so many people die before me, although I understand that God’s desire must be obeyed, that He owns everything and what He lends us only so far.” as long as He loves the children He gives us.” Death of himself youngest son Catherine became a real disaster for her dynastic plans. Henry III had no children, and it seemed unlikely that he would ever have any. According to the Salic Law, the former Huguenot Henry of Bourbon, King of Navarre, became the heir to the French crown.  The behavior of Catherine's youngest daughter, Marguerite de Valois, annoyed her mother just as much as Francois's behavior. One day in 1575, Catherine yelled at Margarita because of rumors that she had a lover. Another time, the king even sent people to kill Marguerite de Bussy’s lover (a friend of François Alençon), but he managed to escape. In 1576, Henry accused Margaret of having an inappropriate relationship with a lady of the court. Later, in her memoirs, Margarita claimed that if it were not for Catherine’s help, Henry would have killed her. In 1582, Margarita returned to the French court without her husband and soon she began to behave very scandalously, changing lovers, Catherine had to resort to the help of the ambassador to appease Henry of Bourbon and return Margarita to Navarre. She reminded her daughter that her own behavior as a wife was impeccable, despite all the provocations. But Margarita was unable to follow her mother's advice. In 1585, after Margaret was rumored to have tried to poison and shoot her husband, she fled Navarre again. This time she headed to her own Agen, from where she soon asked her mother for money, which she received in an amount sufficient for food. However, soon she and her next lover, persecuted by the inhabitants of Agen, had to move to the Karlat fortress. Catherine asked Henry to take immediate action before Margaret disgraced them again. In October 1586, Margarita was locked in the castle d'Usson. Margarita's lover was executed before her eyes. Catherine excluded her daughter from her will and never saw her again.

The behavior of Catherine's youngest daughter, Marguerite de Valois, annoyed her mother just as much as Francois's behavior. One day in 1575, Catherine yelled at Margarita because of rumors that she had a lover. Another time, the king even sent people to kill Marguerite de Bussy’s lover (a friend of François Alençon), but he managed to escape. In 1576, Henry accused Margaret of having an inappropriate relationship with a lady of the court. Later, in her memoirs, Margarita claimed that if it were not for Catherine’s help, Henry would have killed her. In 1582, Margarita returned to the French court without her husband and soon she began to behave very scandalously, changing lovers, Catherine had to resort to the help of the ambassador to appease Henry of Bourbon and return Margarita to Navarre. She reminded her daughter that her own behavior as a wife was impeccable, despite all the provocations. But Margarita was unable to follow her mother's advice. In 1585, after Margaret was rumored to have tried to poison and shoot her husband, she fled Navarre again. This time she headed to her own Agen, from where she soon asked her mother for money, which she received in an amount sufficient for food. However, soon she and her next lover, persecuted by the inhabitants of Agen, had to move to the Karlat fortress. Catherine asked Henry to take immediate action before Margaret disgraced them again. In October 1586, Margarita was locked in the castle d'Usson. Margarita's lover was executed before her eyes. Catherine excluded her daughter from her will and never saw her again.  In 1588 the culmination of the religious wars began. There was a whiff of rebellion in Paris. Leaflets about “His Majesty the Hermaphrodite” appeared, and an image of the Queen Mother, that “old witch” who gave birth to a perverted son, was burned. The day came when cries were heard in front of the Louvre: “Down with Valois! Death to Valois! Thus, for the first time in a thousand years, the throne of France began to shake. With the knowledge of Henry III, Cardinal de Guise was killed, he was brutally stabbed to death, his body was thrown next to the body of his brother, both corpses were cut into pieces and burned in the fireplace of the castle, so that later they would not be worshiped as martyrs. As soon as Guise was sent to the next world, the king went down to his mother, who occupied the apartment under his own and who, most likely, should have heard the noise at the time of the murder. At the patient's bedside sat the doctor Filipe Cavriana, a spy for the Grand Duke of Tuscany, to whom he told about this scene. Henry asked him how the queen was feeling. The doctor told him that she was resting after taking medication. Then the king approached old woman and greeted her very confidently: “Good afternoon, Madam, excuse me. Monsieur de Guise is dead; There's no point in talking about him anymore. I ordered him to be killed, ahead of his intentions towards me.” He recalled what insults he had to endure, and all that he knew about the incessant intrigues of his enemy. To save his power, his life and his state, he had to take these extreme measures. God himself helped him in this; With that, he took his leave, telling his mother that he was going to mass to thank heaven for the happy outcome of this punishment. “I want to be a king, and not a prisoner and a slave, as I was, from May 13 until this hour, when I again become a king and master.” With these words he left. The Queen was too weak to answer him. “She almost died,” said the doctor, “from terrible grief,” and adds: “I am afraid that the departure of Madame Princess of Lorraine [to Tuscany] and this funeral of the Duke of Guise may worsen her condition.” On the morning of January 5, on the eve of Epiphany, she wanted to write a will and confess. She lived out her last minutes. Her loved ones were worried. Let us give the floor to the eyewitness of this event, Etienne Pasquier: “There is something remarkable in her death. She always had great faith in fortune tellers, and since she had once been told that in order to live long she had to beware of some Saint Germain, she especially did not want to go to Saint Germain-en-Laye, for fear of meeting her death, and even, in order not to live in the Louvre, which belongs to the parish of Saint-Germain de l'Auxerrois, she ordered the construction of her palace in the parish of Saint-Eustache, where she lived. Finally, God wanted that, dying, she did not live in Saint-Germain, but the first confessor of the king, de Saint-Germain, became her comforter." An autopsy of the corpse revealed a terrible general condition of the lungs with a purulent abscess on the left side. According to modern researchers, possible reason Catherine de Medici's death was due to pleurisy. “Those who were close to her believed that her life was shortened by frustration because of the actions of her son,” believed one of the chroniclers. Since Paris was held by enemies of the crown at that time, they decided to bury Catherine in Blois. She was later reburied in the Parisian Abbey of Saint-Denis. In 1793, during the Great french revolution, the revolutionary crowd threw her remains, as well as the remains of all French kings and queens, into a common grave

In 1588 the culmination of the religious wars began. There was a whiff of rebellion in Paris. Leaflets about “His Majesty the Hermaphrodite” appeared, and an image of the Queen Mother, that “old witch” who gave birth to a perverted son, was burned. The day came when cries were heard in front of the Louvre: “Down with Valois! Death to Valois! Thus, for the first time in a thousand years, the throne of France began to shake. With the knowledge of Henry III, Cardinal de Guise was killed, he was brutally stabbed to death, his body was thrown next to the body of his brother, both corpses were cut into pieces and burned in the fireplace of the castle, so that later they would not be worshiped as martyrs. As soon as Guise was sent to the next world, the king went down to his mother, who occupied the apartment under his own and who, most likely, should have heard the noise at the time of the murder. At the patient's bedside sat the doctor Filipe Cavriana, a spy for the Grand Duke of Tuscany, to whom he told about this scene. Henry asked him how the queen was feeling. The doctor told him that she was resting after taking medication. Then the king approached old woman and greeted her very confidently: “Good afternoon, Madam, excuse me. Monsieur de Guise is dead; There's no point in talking about him anymore. I ordered him to be killed, ahead of his intentions towards me.” He recalled what insults he had to endure, and all that he knew about the incessant intrigues of his enemy. To save his power, his life and his state, he had to take these extreme measures. God himself helped him in this; With that, he took his leave, telling his mother that he was going to mass to thank heaven for the happy outcome of this punishment. “I want to be a king, and not a prisoner and a slave, as I was, from May 13 until this hour, when I again become a king and master.” With these words he left. The Queen was too weak to answer him. “She almost died,” said the doctor, “from terrible grief,” and adds: “I am afraid that the departure of Madame Princess of Lorraine [to Tuscany] and this funeral of the Duke of Guise may worsen her condition.” On the morning of January 5, on the eve of Epiphany, she wanted to write a will and confess. She lived out her last minutes. Her loved ones were worried. Let us give the floor to the eyewitness of this event, Etienne Pasquier: “There is something remarkable in her death. She always had great faith in fortune tellers, and since she had once been told that in order to live long she had to beware of some Saint Germain, she especially did not want to go to Saint Germain-en-Laye, for fear of meeting her death, and even, in order not to live in the Louvre, which belongs to the parish of Saint-Germain de l'Auxerrois, she ordered the construction of her palace in the parish of Saint-Eustache, where she lived. Finally, God wanted that, dying, she did not live in Saint-Germain, but the first confessor of the king, de Saint-Germain, became her comforter." An autopsy of the corpse revealed a terrible general condition of the lungs with a purulent abscess on the left side. According to modern researchers, possible reason Catherine de Medici's death was due to pleurisy. “Those who were close to her believed that her life was shortened by frustration because of the actions of her son,” believed one of the chroniclers. Since Paris was held by enemies of the crown at that time, they decided to bury Catherine in Blois. She was later reburied in the Parisian Abbey of Saint-Denis. In 1793, during the Great french revolution, the revolutionary crowd threw her remains, as well as the remains of all French kings and queens, into a common grave  Eight months after Catherine's death, everything that she so strived for and dreamed of during her life was reduced to zero when the religious fanatic monk Jacques Clement stabbed to death her beloved son and the last Valois, Henry III. The servant reported that Catherine, just before her death, quietly said: “I was crushed by the rubble of the house.” Sources.

Eight months after Catherine's death, everything that she so strived for and dreamed of during her life was reduced to zero when the religious fanatic monk Jacques Clement stabbed to death her beloved son and the last Valois, Henry III. The servant reported that Catherine, just before her death, quietly said: “I was crushed by the rubble of the house.” Sources.

At the age of 14, Catherine was married to Henry de Valois, the second son of Francis I, King of France, for whom this union was beneficial primarily due to the support that the Pope could provide to his military campaigns in Italy.

The bride's dowry amounted to 130,000 ducats, and extensive possessions that included Pisa, Livorno and Parma.

Contemporaries described Elizabeth as a slender red-haired girl, short in stature and with a rather ugly face, but very expressive eyes - a Medici family trait.

Young Catherine so wanted to impress the exquisite French court that she resorted to the help of one of the most famous Florentine craftsmen, who made high-heeled shoes especially for her petite customer. It must be admitted that Catherine achieved what she wanted; her presentation to the French court created a real success.

The wedding took place on October 28, 1533 in Marseille.

Europe has not seen such a gathering of representatives of the highest clergy, perhaps, since the days of medieval cathedrals: Pope Clement VII himself attended the ceremony, accompanied by his many cardinals. The celebration was followed by 34 days of continuous feasts and balls.

However, the holidays soon died down, and Catherine was left alone with her new role.